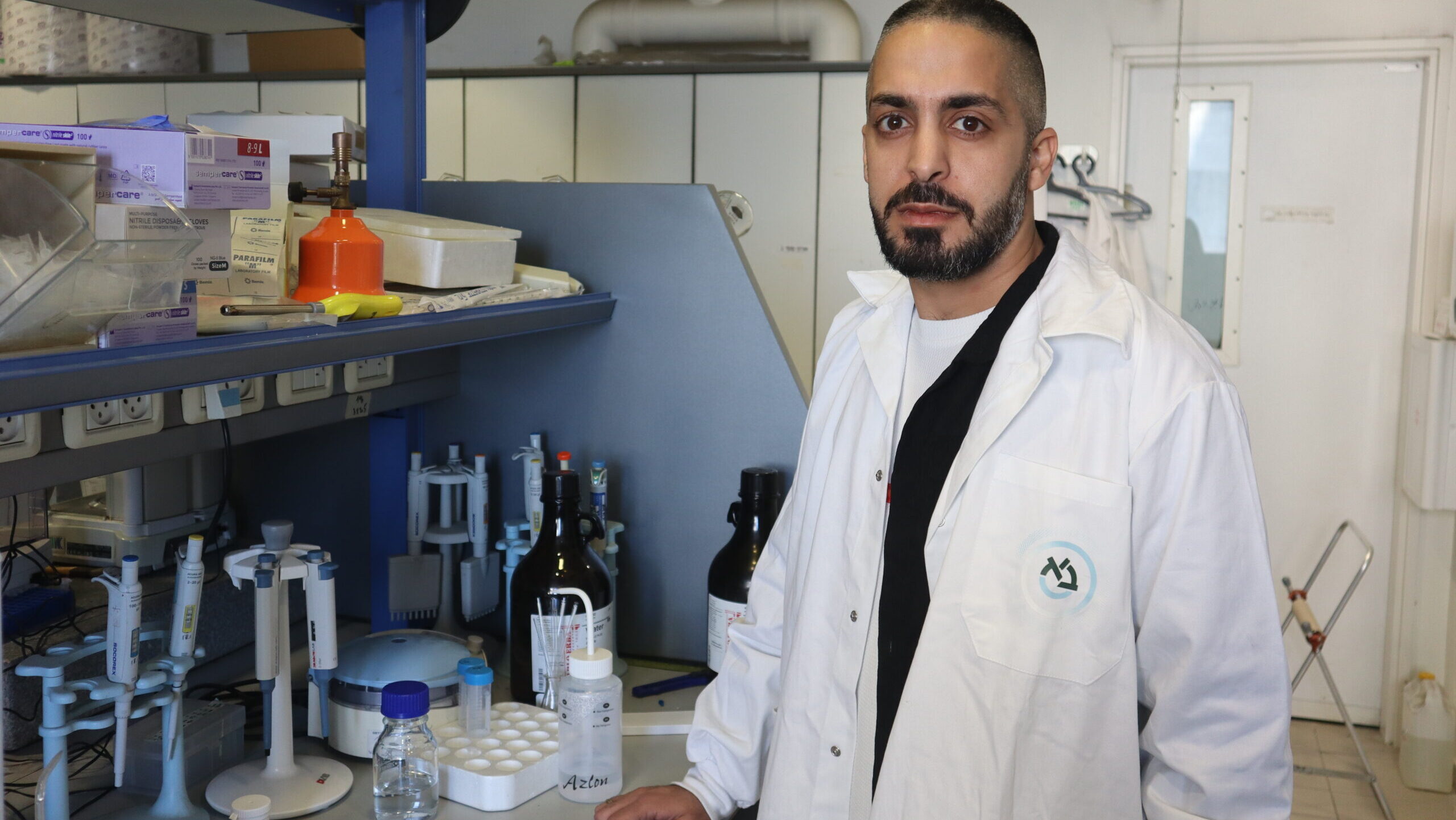

Bilal Abu Salha, a doctoral student at Israel’s Bar Ilan University, has found a way to extend the shelf life of fresh fruit and vegetables by some two weeks, potentially discovering a solution to massively reduce food waste.

“Our research produced amazing results,” Abu Salha told The Media Line. “In our initial research, where we started with strawberries, we extended the shelf-life by over a week … two weeks. And its nutritional value was preserved, as was its smell and freshness.”

This is good news for global markets, grocery chains, and consumers’ pockets. Americans alone waste more than $408 billion annually on food, according to the Feeding America non-profit—including the American family’s average loss of $1600 worth of produce each year.

The solution is twofold—the first is in the material used to coat and protect the produce, and the second is in attaching the coating without chemicals.

Regarding the former, Abu Salha says he focused primarily on using chitosan, an edible, organic, non-toxic, antibacterial, and biodegradable material derived from chitin, polysaccharides, and proteins.

Chitosan is also flavorless, so it does not affect the taste of the products on which it is used—particularly when considering how thin the nano-coating is.

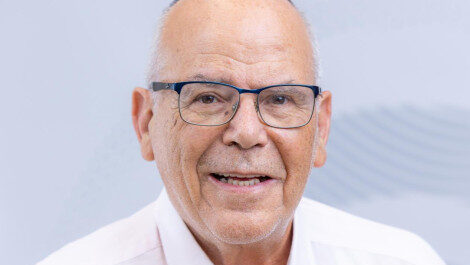

Dr. Ilana Perelshtein—who supervises Abu Salha’s lab work under Professor Aharon Gedanken in the department of chemistry at Bar-Ilan University—told The Media Line that chitosan can be extracted from shrimps and mushrooms, that it has known antibacterial properties. In fact, Abu Salha’s work piggy-backs off her own study.

Several years ago, Perelshtein and Gedanken tried using chitosan and a number of other materials to create antibacterial packaging. “So we took this initial data and results and just converted it into [using it for] direct coating on foods” for the sake of Bilal’s research.

Give the gift of hope

We practice what we preach:

accurate, fearless journalism. But we can't do it alone.

- On the ground in Gaza, Syria, Israel, Egypt, Pakistan, and more

- Our program trained more than 100 journalists

- Calling out fake news and reporting real facts

- On the ground in Gaza, Syria, Israel, Egypt, Pakistan, and more

- Our program trained more than 100 journalists

- Calling out fake news and reporting real facts

Join us.

Support The Media Line. Save democracy.

What is “Sonication?”

Regarding the latter half of Abu Salha’s solution, the method of attaching chitosan is no less important. This process uses the unique sonication method, or in this case, “ultra-sonication,” developed by Professor Gedanken.

The sonication process works by bombarding a liquid solution filled with chitosan with high-frequency sound waves until the solution swirls rapidly and produces masses of microscopic bubbles, which form and immediately implode.

When this process is done along a solid surface—the surface of fresh fruit and vegetables, for example—liquid streams from the implosion eject chitosan particles at incredibly high speeds, embedding them into the food.

The process is permanent, and the embedded particles cannot be removed, even by washing the produce. In this way, the surface of the fruit and vegetables can adopt properties they didn’t previously have—like resistance to bacteria and fungi.

With this resistance, after figuring out the minimal concentration of chitosan necessary to fully eradicate bacteria, the shelf life of treated strawberries was extended by 15 days.

Additionally, Abu Salha says, “The coating itself is categorized as a ‘green chemical.’ It’s very environmentally friendly because the attachment process we use is not a chemical attachment. It’s physical.”

Why Strawberries?

Abu Salha began studying for his doctoral work under Professor Gedanken. But the reason he began to focus specifically on extending the shelf life of food lies in some light-hearted laboratory teasing.

That said, “we weren’t only messing around,” Abu Salha says. “When I got to [Prof.] Aharon [Gedanken], I told him I was from the north, and then he learned more about me, including that I came from a mostly agricultural community. So he said, ‘I’ll let you focus on extending the shelf-life of fresh produce and other edible products.’ The joke was that maybe I’ll have a future in what I was already doing before.”

And as if to add to the joke, Abu Salha began his study with strawberries at his family’s strawberry nursery in northern Israel’s Golan Heights.

But when the initial results came back positive, the joke faded into excitement.

“Gedanken wondered what would happen if we coated the fruits directly,” says Perelshtein, adding, “I said the fruit will not survive the ultrasound. For me, it was very strange to put something under ultrasonic waves. But after we tried it and saw the fruits were stable—that it worked—we continued with this research. … I’m proud that we didn’t give up in the beginning and brought this idea, this vision, to reality.”

As of now, Abu Salha and the team have experimented with many different fresh fruits and vegetables, including tomatoes, mushrooms, and potatoes, and the results appear consistent.

In protecting his doctorate, however, Abu Salha declined to provide too much data before he published, as revealing it prematurely could put his PhD at risk.