Soon-to-be-published memoir by Dita Kraus details harrowing childhood experience guarding precious books; provides rare glimpse into the family camp in Auschwitz

Dita Kraus was 14 years old when she was given a most unusual task in World War II’s largest and most notorious concentration camp: Manage and distribute a clandestine collection of books among the prisoners in Auschwitz’s so-called family camp.

In a new first-hand account of her experiences, Kraus reveals the harrowing daily workings of the Theresienstadt family camp and the children’s block, and describes how she and her mother struggled to survive. Titled A Delayed Life: The True Story of the Librarian of Auschwitz (Ebury Press), Kraus’ memoir is scheduled to be released in early February.

“When I was 10 [years old], I had to delay all my wishes and all my plans,” Kraus explained to The Media Line in relation to the book’s title. “Everything had to be postponed until, until, until… This went on and on.”

Born in Prague in 1929, Dita Kraus (née Polachova) came from a secular socialist family and as a young child was disconnected from her Jewish identity.

“I came across the word ‘Jew’ for the first time when I was in grade three,” she writes in her memoir.

When she was 10, war broke out and Nazi Germany occupied then-Czechoslovakia. Kraus’ father was dismissed from his job and a growing number of restrictions were placed on the country’s Jewish community until 1942, when the family was deported to the Theresienstadt Ghetto. Over 150,000 Jews passed through the ghetto, which was established by the SS. All of its residents lived in squalid conditions. Most were then sent off in transports to Nazi concentration camps.

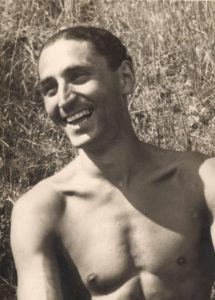

A photo of Dita Kraus as a child, taken in 1942. (Courtesy)

In 1943, at the age of 14, Kraus and her family were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Like other Jews from Theresienstadt, they were sent to the BIIb compound, or family camp, consisting of 32 barracks where men and women slept separately.

A view of the ruins of the BIIb compound or family camp in Auschwitz-Birkenau. (Wikimedia Commons)

The Library of Auschwitz

The family camp was a unique phenomenon in Auschwitz. Unlike the vast majority of those in the infamous Nazi camp, who were separated from family members upon their arrival, 17,500 Czech Jews from Theresienstadt were afforded singular privileges in the family camp, including being able to remain together.

Give the gift of hope

We practice what we preach:

accurate, fearless journalism. But we can't do it alone.

- On the ground in Gaza, Syria, Israel, Egypt, Pakistan, and more

- Our program trained more than 100 journalists

- Calling out fake news and reporting real facts

- On the ground in Gaza, Syria, Israel, Egypt, Pakistan, and more

- Our program trained more than 100 journalists

- Calling out fake news and reporting real facts

Join us.

Support The Media Line. Save democracy.

“Men, women and children were in the same camp [and] we could meet outdoors,” Kraus told The Media Line. “There was a daycare which was run by Fredy Hirsch, a marvelous person. It was a miracle that he was allowed to keep one house free [to be used as] a daycare for children.”

Teacher and Zionist youth movement leader Fredy Hirsch, who ran the children’s block in Auschwitz-Birkenau. (Beit Terezin Archive)

Hirsch, a teacher and Zionist youth movement leader, ran the children’s block and somehow convinced the SS to allow the barrack to be dedicated to children during the daytime, thereby creating the only educational oasis of its kind in Auschwitz. Hirsch also appointed Kraus to be the librarian of the “smallest library in the world.”

“I became responsible for the few books that were there,” Kraus said, adding that the collection consisted of a dozen or so tomes, including an atlas and a Russian-language instruction book. The books were smuggled into the children’s block from the luggage of Jews who arrived to Auschwitz daily. Whenever a book was found, it would be sent there.

“The [books] were not entertaining,” Kraus recalled. Nevertheless, they “were carefully handled and cherished and always came back in good order.”

In addition to the small library, some of the adults also served as “living books.” Much of the instruction was done under the radar, with camp officials being told that the children were learning German or playing games.

“My husband was one of the [educators] in the children’s block,” Kraus explained. “He and other adults who remembered stories like Robinson Crusoe, Gulliver’s Travels or The Count of Monte Cristo went from one group [of children divided by age group] to another, and in installments [they] would tell them a chapter. There were no other materials [available]. It was all oral.”

No documentation exists that explains the reasoning behind the creation of the Theresienstadt family camp and it has been much debated by historians. In 2002, the Czech-Israeli writer and Auschwitz family camp survivor Ruth Bondy described the children’s block as a “strange and wonderful enclave.”

In her 2002 essay “Games in the Shadow of the Crematoria” (translated from the original Hebrew), she wrote that “so far, no official documents that attest to its existence have been found in the German archives. It is as if there never was a children’s block. The children’s singing has been swept away by the wind.”

Still, despite the incredible privileges afforded to the Czech prisoners in this compound, they suffered from cold, starvation, illness and a mortality rate comparable to other parts of Auschwitz-Birkenau.

“We were all hungry and were aware that our lives would end in a few months in the gas chambers,” Kraus told The Media Line.

A Chilling Encounter with Dr. Mengele

In March 1944, the Nazis began liquidating the family camp and sent more than half of the prisoners to die in the gas chambers. Kraus and others were expected to go the same route; however, the Germans decided to send some of the remaining survivors who were still able-bodied and somewhat healthy to Germany for forced labor.

Kraus recalls how a chilling encounter with the notorious Dr. Mengele would allow her to narrowly escape the fate of thousands of others in the family camp.

“I was chosen by Dr. Mengele together with 1,500 women to be sent to Germany to work and that’s how we survived,” Kraus said. “We were sent to slave labor.”

Beyond the book’s invaluable Holocaust testimony, including Kraus’ imprisonment in various labor camps across Germany as well as her experiences in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, the memoir also details her encounter with her future husband, Otto Kraus, after the war and how the two immigrated to Israel in 1949 shortly after the state’s establishment. Kraus further discusses her love of painting, which began under the well-known artist and educator Friedl Dicker-Brandeis, who taught her in the Theresienstadt Ghetto.

A photo of Dita Kraus in her home in Israel, taken recently. (Courtesy)

But the incredible story of the children’s block and its tiny library is perhaps the most inspiring element of Kraus’ memoir.

“Most of the staff on the Kinderblock [children’s block] were men and women barely 20 years old,” Kraus writes in her book. “They were aware of their approaching death and must have been terrified. Yet they spent their remaining days with the children, creating for them a kind of haven in this hell. They are, in my eyes, the real heroes of Auschwitz.”

A Delayed Life: The True Story of the Librarian of Auschwitz will be released by Penguin Books on February 6, 2020, and will also be available for purchase from Amazon.com on February 11.