Being listed in the popular navigation application seems to be the exception rather than the rule for Palestinian-owned businesses

When 18-year-old law student Suleiman Abbasi decides to go to his favorite hookah bar in Jerusalem’s Old City, he doesn’t check his phone for directions, bus timings or traffic as has become the norm across North America. The Jerusalem native doesn’t need online help in plotting his journey.

“We’re used to the places; we decide where to go before I get up from my house,” he told The Media Line. “For example, if I want to buy a hookah for my home, we have 10 shops or more around the Old City. On this street, you might find two or three shops.”

He knows the places by heart, living in the Beit Hanina neighborhood of Jerusalem, north of the Old City and on the road to Ramallah. Abbasi lives in an area a half-hour commute by train or bus to the walls of the Old City.

He makes the regular journey to come here specifically to Badran’s, a quaint local hookah bar that uses fresh flavors and still serves customers with coals heated by hand. Run by Old City native Aatef Badran, it’s a popular spot among Old City residents and visitors alike.

Badran’s on a Saturday night, March 7, 2020. (Shakir Rimzy)

But if you don’t know Badran’s exists, you won’t find it at all. The store isn’t listed anywhere on Google’s services – and that’s not for lack of trying, says the proprietor Aatef.

“I did the online listing on Google,” he says, “but after a few days, it didn’t stay, and the shop wasn’t there. I took pictures and gave the hours and told the prices and everything.”

He thought about listing the business on Google Maps so tourists in the various hotels across the city would know that he’s open after all the other stores have closed.

“I get Jewish people, Christian people, people who live in the Old City, but not many tourists,” he told The Media Line.

As owner of one of the few late-night establishments open in the Old City, he doesn’t understand why his store isn’t listed. The after-hours hookah, juice and sandwich bar isn’t the only business not listed on Google’s mapping service. Being listed seems to be the exception rather than the rule for Palestinian-owned businesses.

“There’s one store listed online, and beside it, you have 10 stores selling the same thing,” says Abbasi about his neighborhood of Beit Hanina.

Over the decades, the neighborhood has become a popular spot among Palestinian and Israeli Arabs. Today it contains a wide range of shops selling everything from baklava, shawarma and fresh juice to household cleaning supplies and electronics. Countless stores dot the main road passing through to the Beit Hanina checkpoint that leads to the West Bank.

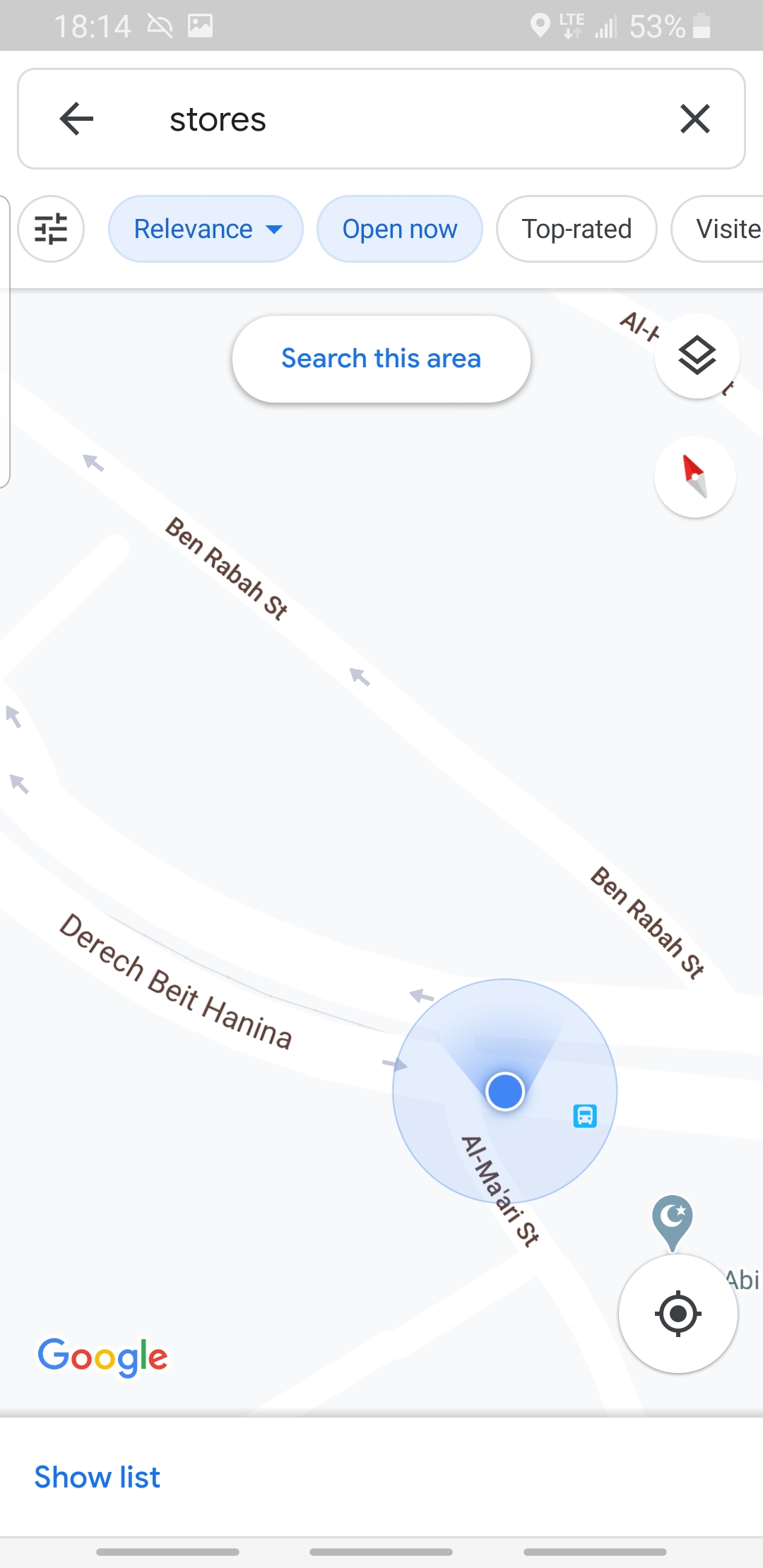

But that’s not an impression a traveler who is only relying on Google Maps will get; a search for “stores” in English on the app will yield far fewer results than the reality of business in the neighborhood.

Map view of Beit Hanina, March 6, 2020. (Screenshot: Google Maps)

Street view of same Beit Hanina location, March 19, 2020. (Screenshot: Google Maps)

While Beit Hanina is within Jerusalem’s municipal boundaries, the difference between the neighborhoods is akin to hopping over a border. The spoken language changes, as does the script on signs hanging over the entrances to stores. But there’s no separate visa required, only a transit card or taxi going up the slopes.

These changes also carry over to the digital world, as Arab businesses appear less frequently than do Jewish businesses in the adjacent Pisgat Ze’ev community.

According to Abbasi, this can be explained not by anything malicious but rather the fact that Palestinian businesses have Palestinian customers like himself who have different needs.

“They don’t need it [Google Maps]. The country is pretty small, they know the places, everyone has their favorite shops. For my clothes, I have my favorite shop to buy from, and you make friends with the sellers,” he told The Media Line.

Culture and familiarity, he says, have a strong part in it.

One seller who is quite popular among Palestinian residents is Abu Yazan Abdeen Commercial Stores in the Old City. A household name among Palestinians in the Old City, for over three generations it’s been a go-to place for kitchen appliances and household goods. Abdeen, the third-generation owner of the family business, told The Media Line that he thinks there’s another reason why Google Maps isn’t quite as popular among Palestinians: because of the role of Facebook.

The third-generation owner of Abu Yazan Abdeen Commercial Stores outside his store, March 4, 2020. (Shakir Rimzy)

“Business for Palestinians is like family, you get to know the people who come to the store, you know about their families, their children, you keep up with them. Facebook becomes a way for that.”

In a 2017 social media study done by Concepts Technologies in partnership with the Bank of Palestine and Paltel, one of the West Bank’s largest Telecom providers, reported that Facebook was the most used online application for Palestinians on both sides of the Green Line and that it was the main facilitator for news and services.

Dr. Villy Abraham, a consumer behavior expert at Sapir Academic College, told The Media Line that in the context of online shopping, “Israeli Jews shop more online than Palestinian or Arab Israelis due to greater access to internet infrastructure and access to computers and smartphones.”

Online shopping is a further evolution of an online economy that begins when businesses in the area are part of an online marketplace. If a business isn’t listed online, then e-commerce cannot proliferate.

Access to internet infrastructure with smartphones can lead to more businesses having an online footprint.

But as for Google and its mapping service, its function isn’t a necessity for Palestinians quite yet as, for some, there are simpler solutions.

For Abbasi it’s quite simple: When asked why he doesn’t use Google Maps very often, he gestures to his friend sitting across from him at the hookah bar and says, “He’s my Google Maps.”

Shakir Rimzy is a student in The Media Line’s Press and Policy Student Program.