Jerusalem Biennale pilot artist in residency program brings contemporary Jewish artists to Jerusalem

In a corner, light-filled studio, adjacent to the chaotic Machane Yehuda fruit and vegetable market in downtown Jerusalem, you can find Lenore Cohen, 26, a Syrian-Jewish artist from Brooklyn, practicing her Arabic calligraphy.

In a corner, light-filled studio, adjacent to the chaotic Machane Yehuda fruit and vegetable market in downtown Jerusalem, you can find Lenore Cohen, 26, a Syrian-Jewish artist from Brooklyn, practicing her Arabic calligraphy.

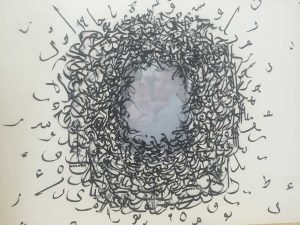

Using black or gold ink, Cohen traces the letters with handmade bamboo calligraphy pens in varying sizes on thin white translucent paper, which she saves and posts on the wall with blue tape for later reference. She’s working on a project called “What We Forgot.”

Cohen takes ancient Arabic proverbs that her father used to read to her and reworks them to apply to modern life. These popular phrases were used by her Syrian community for hundreds of years, but have fallen out of use. Cohen keeps a running Google document with all of the phrases, which she constantly updates with new notes as she ruminates on the phrases until she deciphers their deeper meanings, which then, often, inspire a work of art.

“What does this remind me of, what’s a way I can make this applicable today, what’s a way I can illustrate this phrase, what’s another layer of meaning I can add to this?” Cohen asks. “Because they are so multifaceted and touch on literally every aspect of life, something will come up and then you’re like ‘oh, that’s the phrase!’”

“There is a lot of timeless wisdom in there that would do us all some good to remember,” Cohen said.

For example, Cohen talks about one phrase she has turned into a piece of art: “To the intelligent, a hint is sufficient.” She says she has envisioned an illustration of soldiers standing guard at Jaffa Gate, a gate to the Old City in Jerusalem frequented by Jewish visitors that has been the site of several Palestinian terrorist attacks. Israeli soldiers must remain attentive to every little movement and any small hint could signify something big, therefore, to the intelligent (the soldiers), any hint (any sighting or movement) is sufficient enough evidence.

Another phrase, “I visited the Sultan’s palace, but my home is best,” prompted the artist to create a graffiti style piece of art featuring a crooked street in the Nachlaot neighborhood in Jerusalem, the original Syrian neighborhood in the city, which she frequents. So, while Cohen may have visited historic monuments or areas, such as the Western Wall, arguably the holiest site for Jews, Christians, and Muslims alike, walking through the Nachlaot neighborhood of her ancestors makes her feel much more at home.

“They come from the Middle East but they aren’t so Middle East specific,” Cohen says. “What is so much fun about this series is that now I am taking my New York contemporary brain of the modern world and I am taking these really old things and saying, ‘okay, how do we make them new now, how do we illustrate to everyone that they are still relevant?’”

Her art is not kitschy, nor is it so modern that it is undecipherable by those who are not art aficionados. Instead, it is poignant, simply beautiful, and thoughtful. Cohen takes her time, reflecting on the proverbs, until she finds a way to make them applicable.

Positioned on her desk, Cohen has taken a 1610 painting “Susanna and the Elders” by Atermisia Gentilischi, which depicts the biblical story of Susanna, a woman who was sexually harassed in her community. The painting shows the men conspiring against her as Susanna sits repulsed and scared. Cohen then superimposed the infamous “modesty sign” from Mea Shearim, an ultra-orthodox neighborhood in Jerusalem, which asks women and girls to “not disturb the sanctity of our neighborhood and our way of life as Jews committed to God and his Torah” by passing “through our neighborhood in immodest clothes.”

Next to the photo-shopped painting, Cohen added a pillar with the proverb, “he who can’t dance says the floor is crooked,” written in Arabic calligraphy running up and down the pillar.

This holiday season, give to:

Truth and understanding

The Media Line's intrepid correspondents are in Israel, Gaza, Lebanon, Syria and Pakistan providing first-person reporting.

They all said they cover it.

We see it.

We report with just one agenda: the truth.

She is a type of journalist in her own right – a sort of mediator of time – as she delicately intertwines the phrases of her Syrian past with the political, social, and cultural landscape of her Jewish present.

“We aren’t just ourselves,” Cohen says. “Whether we like to admit it or not, everyone is a sum of a few parts and, to be in touch with those roots is so important because it informs your life moving forward and enriches your experience.”

Cohen is in Jerusalem as the first ever artist-in-resident supported by the Jerusalem Biennale for Contemporary Jewish Art. By bridging the gap between Judaism and art, it is attempting to do what Cohen does with her proverbs. The event is part of the Biennial foundation, an international arts organization providing advocacy and thought leadership by supporting art events, like the Jerusalem Biennale, all over the world.

“We decided to dedicate the Jerusalem Biennale to a narrow field, which is called contemporary Jewish art,” Rami Ozeri, founding director of the Jerusalem Biennale, who also invited Cohen to Jerusalem, told The Media Line. “I think that it’s the only platform in the world dedicated to it – meaning the intersection of contemporary art and the Jewish world.”

Contemporary Jewish art is not the most recognizable type of art. Many are familiar with Jewish art, often characterizing it as Judaica because of its biblical nature, and with with contemporary art, which is defined as art that is relevant to today. Contemporary Jewish art is something new, something that Ozeri is credited with bringing attention to in a city more known for religion and Judaica than contemporary art.

“It’s a small field, but Jerusalem has the biggest advantage when it comes to this field (as it) is the center of the Jewish people,” Ozeri added.

Ozeri is not alone in his love and interest in furthering the culture of Jerusalem. This is why Cohen is working in a shared studio in the old French Alliance or Alliance Française building, which housed the Alliance School, a Jewish trade school founded in 1882. It is also the same school that her grandfather graduated from in 1925. The formerly abandoned building is now a multidisciplinary center used to house artists, dancers, non-profits, government employees, and Cohen.

When Ozeri imagined the artist-in-residency program, he immediately invited Cohen to participate, realizing that being in a city like Jerusalem with the backing of this program, Cohen would be able to truly come into her own as a Jewish contemporary artist.

From meetings with museum directors to sessions with Arabic calligraphers, being in Jerusalem has offered Cohen the chance to not only expand her repertoire but also to be in, feel and explore, the city so central to her art.

“It’s where the work is most meaningful,” Cohen said.

Being a contemporary Jewish artist is not something Cohen, who studied art at Brooklyn College, had ever related to. After graduating from college, she was mostly focused on selling her art.

“I didn’t use to do work like this at all – it used to be a lot more decorative and abstract because I was concerned with selling it,” Cohen said. “But also, because I was younger, I didn’t really feel like I had anything to say with my art that was worth saying.”

However, once Cohen realized that institutions like the Jerusalem Biennale existed, it prompted the artist to explore her Syrian-Jewish roots, a side of her that had always been humming in the background, waiting to be further explored.

Cohen, whose Jewish identity guides everything she does, believes it is really important that the Biennale is giving contemporary Jewish art, like hers, a voice.

“It definitely got me thinking like ‘okay, maybe this stuff is interesting, and if I could find a platform to actually display it, maybe it is worth exploring,” Cohen said. “I never would have pictured myself as the Jewish artist.”

Katie Beiter is a student journalist at The Media Line