Down in the Negev desert city of Eilat—Israel’s picturesque resort town on the Red Sea, nestled between Egypt and Jordan on the southernmost tip of Israel—residents and businesses alike are coming together to serve as a repository for refugees.

An estimated 500,000 Israelis have been internally displaced since October 7. Many fled the Hamas terrorists’ massacre of some 1,400+ (mostly civilian) people, and many more were uprooted by the Israeli Defense Forces both around Gaza and along Israel’s northern borders with Lebanon and Syria to make way for a secure operational war zone.

Among the displaced are some 70,000 civilians who have relocated to this tourist city—more than doubling the population of Eilat. But far from the normal holiday atmosphere, the overflowing streets and hotels are filled with a somber tone.

“They didn’t come to relax or for tourism or fun,” said Eilat Mayor Eli Lankri, speaking to The Media Line. Their every need must be taken care of, including humanitarian aid, he continued to explain. To that end, some 26 centers for humanitarian relief have been erected, including healthcare centers manned by volunteers from central Israel.

Eilat Mayor Eli Lankri. (Aaron Poris/The Media Line)

“We are [also] assisting them with the education network for children. There are some 15,000 to 16,000 extra children, maybe more, and we absorbed them into our school system; and now we’re building a school especially for them, from caravans,” Mayor Lankri said, adding that this effort includes a kindergarten made from tents.

“We’re building a whole city, here, in order to receive them. How long it will take, I don’t know. But it’ll take whatever it takes. We’ll do everything. If it takes weeks, or months, we’re here for them,” continued the mayor.

Still, many displaced Israelis arrived in Eilat with nothing but the clothes, or pajamas, on their backs—and often out of touch with their families. In many cases, the displaced only learned of the fate of their loved ones and community members—whether they were killed, missing, or kidnapped—after arriving in Eilat. So, mental healthcare, in addition to the physical needs of the displaced, has been a priority—and the whole city has pitched in.

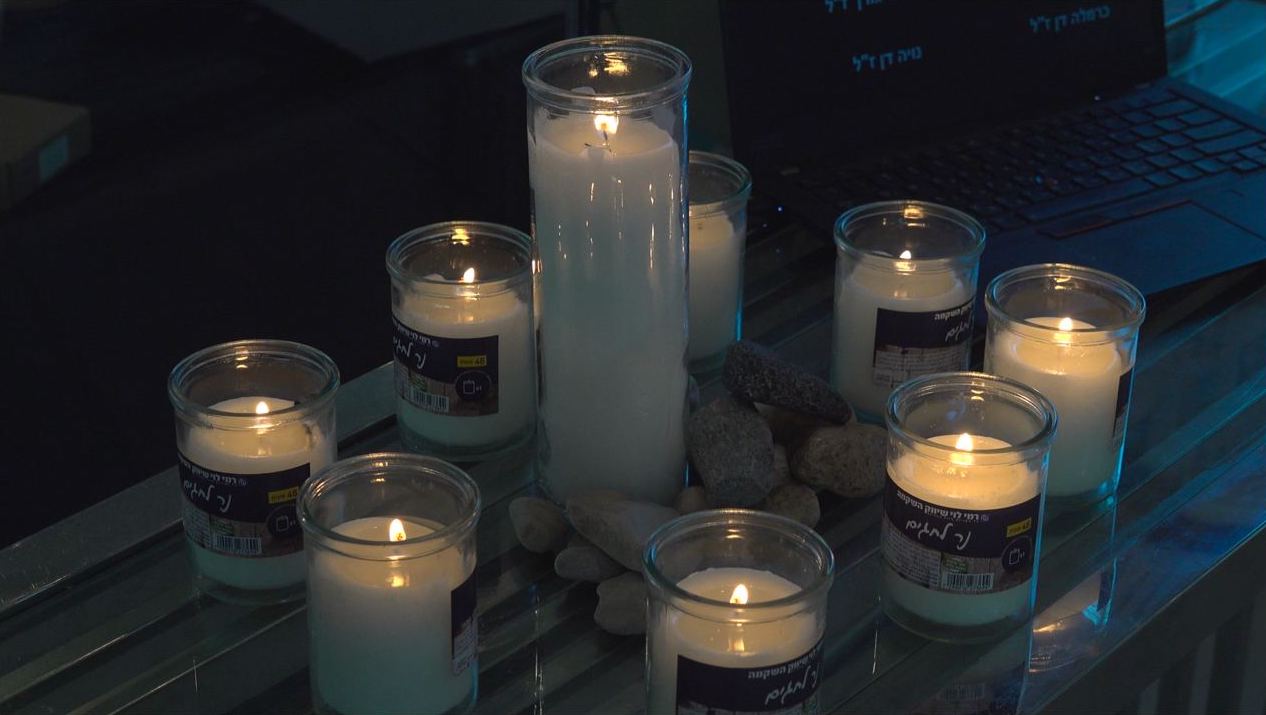

Memorial table at the Isrotel Yam Suf Hotel in Eilat, Israel, for members of Kibbutz Nir Oz who were murdered by Hamas terrorists on Oct. 7, 2023. (Aaron Poris/The Media Line)

Among the volunteers at the Isrotel Yam Suf Hotel is retired hairdresser Sima Matok. “She’s doing God’s work,” a soldier stationed at the hotel told The Media Line.

Matok came out of retirement to provide full-time free services for the many traumatized women at the hotel, many of whom lost loved ones on that tragic day. The hotel is filled to the brim with an average of four to six people per room. The occupants come mainly from Kibbutz Nir Oz, which was ravaged in the Hamas terrorist attack.

“At first, I had to coax them to come and do their hair, if only to bring a smile to their faces for just one day,” Matok told The Media Line. “[But] slowly slowly, I understood that I’m succeeding in opening their hearts. They opened up to me. And in this way, I was able to bring them to a place where they said ‘You don’t know what you’ve done for us. It’s not just our hair. You’re really providing a good feeling that we exist. After everything we went through, everything that happened, everything we saw … at least we can see some humanity.’”

Retired Hairdresser, Sima Matok at the Isrotel Yam Suf Hotel in Eilat, Israel. (Aaron Poris/The Media Line)

In a follow-up interview with The Media Line, Ran Ahinoam, Isrotel’s general manager, added that the hotel is providing many of the children staying there with a pseudo school for a few hours per day. Meanwhile, the adults have psychological staffers to speak with, as well as social workers—many of whom are there every day.

“For the first week after they arrived,” Ahinoam explained, “most residents refused to even leave the hotel altogether. They feared that someone was still outside shooting.”

That said, most of the internally displaced refugees are fighting for a sense of normalcy by taking their day-to-day lives into their own hands. While the government is subsidizing the hotels to keep cleaning and other staff on hand, according to Ahinoam, the refugees came to him at the beginning and said, “‘We don’t want to see you work around and between us … taking our plates and cleaning our rooms. We want to do it alone. We want to feel alive. We don’t want to feel like we’re on vacation because we are not on vacation.’ And until now, they do most things themselves,” he explained.

This holiday season, give to:

Truth and understanding

The Media Line's intrepid correspondents are in Israel, Gaza, Lebanon, Syria and Pakistan providing first-person reporting.

They all said they cover it.

We see it.

We report with just one agenda: the truth.

“We don’t see people playing cards and laughing,” Ahinoam added. “They’re always reading [news] or on their phone, or swimming … [They’re] trying to keep their minds busy.”

Isrotel is far from alone. Every hotel is at full capacity, and most private residents are also hosting guests in their homes.

Even the Aquamarine Hotel, which was closed for over a year, was recently reopened to house some of the internally displaced Israelis. Speaking to The Media Line in the dining hall of the hotel, former mayor of Eilat, Meir Itzhak Halevy, mentioned how his son, Itamar, went about organizing the Aquamarine’s comeback.

Former Eilat Mayor Meir Itzhak Halevy. (Aaron Poris/The Media Line)

“He knew the place where we’re sitting has been closed for a year and a half,” Halevy said. “[So] he called the owner of the hotel, Yaffa, who is also a righteous woman, and said ‘You have 80 rooms. Give them to me.’ She said ‘The hotel isn’t set up, it’s dirty, etc.’ So, he put out a post and within 3 hours, tens of people showed up to clean the hotel.”

Forty-eight hours later, by the second day of the war, some 300 displaced people had arrived from Sderot, Ofakim, Netivot, and Ashkelon. “And all the time, on a voluntary basis, like my righteous Itamar, everyone donates,” Halevy continued. From games for the children to clothing, mattresses and bread for the Sabbath—everything is donated. “Everything so that these people can feel calm,” he added.

Among the volunteers at the Aquamarine is Romi Younger, a 17-year-old pre-med student and volunteer paramedic with the Magen David Adom emergency medical service. “At first, we just came to clean,” she told The Media Line. But now she’s there for some 13 hours a day, doing anything the residents need, including running first aid workshops. Younger’s teachers and parents support her.

Former Eilat Mayor Meir Itzhak Halevy (right), Aaron Poris (center), and volunteer paramedic Romi Younger (left) at the Aquamarine Hotel in Eilat, Israel. (Dario Sanchez,/The Media Line)

“My teacher has a son serving [in the Israel Defense Forces] in Gaza, but she still goes out of her way to help me stay caught up with my schoolwork as well as volunteer,” Younger said.

“These people experienced incredibly difficult things on that damnable day, the 7th of October,” added Halevy, recounting how one woman refused to return to her room on the top floor of the hotel after hearing warplanes overhead. “[So] it is our mission to help them. These are our brethren. This is our job. Here, our strength and resilience are measured. Therefore, we’re all drafted to this mission. … And I’m speaking to anyone who hears me—every person, with the strength God gave them, should assist.”

The city, and indeed the whole nation, seems to have adopted this same mentality. And nowhere in Eilat is this as evident as at The Terminal—the former baggage claim section of the old Eilat airport, which was turned into a theater, and now into a Salvation Army of sorts.

Literal tons of donations have poured in, from children’s toys and baby formula to clothing of all shapes and sizes—free of charge for anyone who is in need. The hope is that the refugees will pay it forward by returning what they no longer need for donation; this is exactly what Eilat local, Liat Grabowski, described as happening.

Liat Grabowski, organizer of The Terminal donation center for internally displaced Israelis in Eilat, Israel. (Aaron Poris/The Media Line)

Speaking with The Media Line among the clothes-covered tables, Grabowski said that she started with Facebook posts and phone calls to organize donations for the incoming displaced Israelis. But as the amount of donations swiftly outgrew her space, she requested permission from the city to expand her operations into The Terminal.

“They gave us this space,” she said, “and since then, we’ve provided broad services for thousands of families. Really amazing people just stuck with me, including people who aren’t working but who chose to do something incredible with their time. And I delegated them to different departments, and we operate like an organization where everyone knows what to do, what’s missing, how to get it, etc. We’re always adapting because this war is changing, and we’re understanding [new] needs and constraints, and so on. We adapt [with the situation],” she added.

Part of the efforts even include deliveries, Grabowski explained, for those too traumatized or infirm to come to The Terminal in person.

“We get lists and have volunteers who collect, volunteers who load their car, volunteers who donate their fuel, and come every day to deliver things where they need to go, to whoever needs it, as much as is needed, and without stopping,” said Grabowski.

“It’s really touching,” added Mayor Lankri. “It warms the heart. We have here a huge demonstration of solidarity, and neighborly love, such as we know exists in Israel. And here it came about and then some.”

But despite the outpouring of support, much more work remains undone. More concerns remain unanswered, and the solutions may lie in past events.

This is not the first time Eilat has absorbed an influx of refugees. The city likewise took in tens of thousands in 2006 during the Second Lebanon War, and former Mayor Halevy said that moving forward, Israel must learn the lessons from this past event.

“In 2006, we surpassed our limits [to host people], and in the end, all the good things we did became problematic. It was a double-edged sword,” he told The Media Line. “We set out to host and got reprimanded. We wanted to help but then more and more people came, and no one wanted to leave. And it can get to the point where you provide problematic services. Even the sewer lines exploded in 2006.”

First and foremost, we don’t have the capacity to feed more people, to host them, to provide them with places to rest.

The fear then, as Israel’s war against Hamas in Gaza escalates, is that cities like Eilat will crumble under the weight of additional waves of displaced Israelis—far exceeding the already surpassed capacity. “First and foremost, we don’t have the capacity to feed more people, to host them, to provide them with places to rest,” Halevy explained.

“The hotels are full. Hostels are full. The citizens of Eilat and the [surrounding] kibbutzes are hosting. We’ve arrived at a situation where we’ve absorbed some 70,000 people but may have to absorb another 30 – 40,000—we’ll be in a bad state. Therefore, the idea in case of emergency is to prepare emergency systems. For example, transforming all the sports stadiums and facilities into protected shelter spaces and spaces to host people. To design temporary enclaves as we go, [and] to ease the flow of all the necessary accessories from mattresses to beds, showers, chemical bathrooms, everything,” he added.

Additionally, Halevy pointed to all the professional manpower that will be needed, from psychologists, social workers, teachers, community center workers, and more; or else, he warned, “the good will turn ugly. The amazing energy that we have today from many, many incredible organizations won’t be able to stand up against the pressures that will arise.”

According to Halevy, “We’re at the start of the road, not the end.”

Meanwhile, Mayor Lankri and city officials do have some plans in place, however, in coordination with Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. “The next step,” he said, “will be to build a city of tents and caravans—as in, to build temporary structures. We are already ready with plans, and the moment it’s decided that it’s necessary, we’ll do it.”