Lebanon War Vets Find Solace in Facebook Group During Pandemic

Nearly 28,000 former military members go to page to express themselves freely, find healing

On Yom Hazikaron, Israel’s memorial day for fallen soldiers and victims of terrorism, the nation comes together to remember those who were lost. However, for the family members of those who have died, and those who fought alongside the deceased, remembering is an everyday process.

This is especially true for the nearly 28,000 soldiers of the newly formed “Stories about what happened at the military post in Lebanon” Facebook group, as translated into English. The private group’s target audience is Israeli soldiers who served in Lebanon between 1983 and 2000, mainly in Israel’s self-declared “South Lebanon Security Zone.”

The invitation-only platform has become a medium in which many soldiers feel comfortable expressing themselves, some for the first time in over 20 years. Some people seek help in healing from war trauma, with people posting the names and numbers of psychologists for those who served. Others find it a venue where they can express themselves freely in a community that understands them without judgment. Family members of fallen soldiers also go to seek stories about their loved ones.

Whatever the reason, one of the group’s ultimate goals is that no one should feel alone. This is especially pronounced during the current coronavirus pandemic, which has left many people feeling lonely and isolated due to quarantine.

Producer and director Eyal Shahar established the group on March 29, initially to conduct research for a dramatic series he was writing. The group, however, quickly caught on, with 10,000 carefully screened participants joining in the first week. Shahar realized that he had created something bigger than himself and the drama series, and left control of the group to people who had served.

“I still have the research but the group is not for my research. It is now a group for people who have been there. My group is now their community where they can share and talk with each other,” Shahar told The Media Line.

“I didn’t expect, because of corona, all of these veterans of the war in south Lebanon to participate,” he added. “There is a 17-year span, so when a soldier who served there in 1999 war born, another soldier had already been in the same place, the same situation, with all the same fears all those years before.”

“I didn’t think people would be so open,” Shahar said.

He is referring to people like Menachem Shechter, one of the managers of the group, who served in Lebanon from 1990 and 1995, and again as an officer in 1997 and 1998.

“Maybe we leave Lebanon, but Lebanon doesn’t leave us,” he told The Media Line. “People have told me they’ve never written about Lebanon before this group because no one wanted to hear.”

“Everyone shares their feelings, how it hurts at night, how they can’t sleep or have nightmares. Almost everyone has a problem. We talk every day. We have a WhatsApp group with over 1,000 messages a day,” he said.

Politicians like Benny Gantz and Naftali Bennett, both of whom were senior officers with combat experience in south Lebanon, have posted on the Facebook page. But, says Shechter, the group is for the “simple soldier” who, he believes, has not been properly acknowledged and supported by the government.

“We hope that the government will recognize us and acknowledge we are still wounded. If they start to help people, it’s going to be great – people who have problems in their souls,” Shechter said.

Shechter also encourages people to write posts about soldiers who have died and share them with the family members they left behind.

This is something personal for Shechter, whose brother was killed in Lebanon in 1996 at the age of 21.

He read of his posts to The Media Line:

“On the day they told us my brother Yishai was killed in Lebanon, my mother and father died, too. My father couldn’t work afterward and my mother, a kindergarten teacher, stopped working as well. My little sister, who was just 11, 12 years old at the time, moved in with my big sister. It was three months before my younger brother’s bar mitzvah and there was no celebration when it happened. People just cried.

Lt. Yishai Shechter, shortly before he was killed in action in southern Lebanon, in 1996. (Courtesy of Menachem Shechter)

“Every day, the hole in our hearts grows bigger. On your wedding day, which is one day of happiness in your life, you sit and think about your brother and what would he have done if he were here. Your mother and your brother cry all day. The happiness grows with every child that is born, but the hole gets bigger, too. You think: Where is your brother? What about the children he would have had, too? When you run, suddenly you shout, ‘Yishai, Yishai, where are you?’ to the sky. When you listen to a song in the car, you start to cry and you don’t know what prompted the tears. …”

“I have a son whom I named Yishai and initially I couldn’t call him by his name. Now I know it’s one of the most important things I’ve done in my life.”

Lt. Lion, who served in Lebanon from 1986 to 1990, contends that the soldiers should not just be portrayed as damaged and that fatalities and deaths need to be looked at in perspective and not personalized.

“You have to understand. What is the price if you don’t fight? Before we were a nation without a country, we were killed without a fight and … I hope that everyone understands that it’s better to die in a fight than without one,” Lion told The Media Line. “We really are happy to pay the price as a nation and if you understand you are part of the nation, it’s OK, you [can’t just] look at it as if it only happened to you, to your brother, to you children. …”

“The sacrifice was of the nation. That’s how we put it into proportion,” he said.

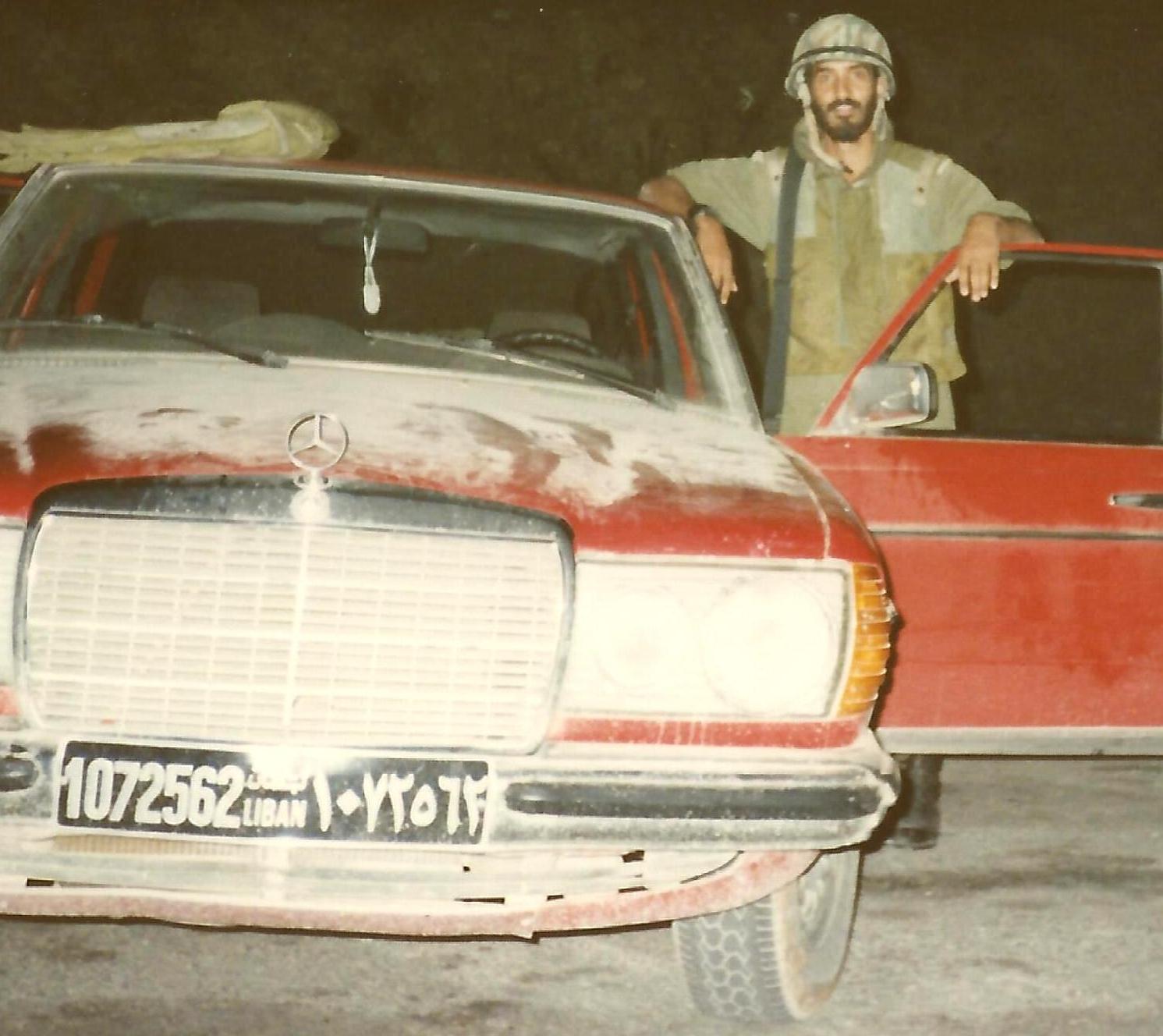

Lt. Lion in Marjaayoun, Lebanon, 1988. (Courtesy of Lt. Lion)

For Lion, having a forum where he can express himself freely, without judgment, is especially important.

“I did things without any orders. I just felt it’s right and I did it. I didn’t feel anybody criticized me, I even got a promotion, so I kept doing what I wanted to do in order to fight the terrorists, the enemy. It was not so difficult, it was fun,” he said. “It went well as long as everything was good, no one asked questions. … It’s very different today.”

This was demonstrated when Lion organized the secret medical evacuation to Israel of a soldier shot by friendly fire when a helicopter didn’t come because of bad weather.

“Your life depends on whether you shoot first; no one helps you. I was an officer there in charge and they asked me to evacuate the soldier to Israel in a chopper. I called for a rescue and I waited for a few minutes and there was no response. … I called again and they told me the helicopter cannot land there. I said: ‘Ok that’s not an answer. I want to know what to do.’”

“This made me crazy … [so] I talked to his commander who … brought him back to Israel that night in an ambulance.”

Lion resigned after this occurred but he always wondered what happened to the soldier he saved. As a result of reaching out to other people and posts on the Facebook group, Lion was able to find someone who thought he knew the soldier. Lion now hopes to meet the man he saved after the coronavirus pandemic is over.

But war isn’t all about saving lives. The taking of lives is a subject that is difficult to understand or discuss except among trusted fellow soldiers.

“Today it is not politically correct to say you enjoyed killing terrorists. There are thousands that we killed there. … I think that lots of people really liked fighting in the war. The most important thing that you get to do as a soldier is facing the threat [your country is facing],” he said. “It’s like the dream of the Jewish people.”

“I see I am not alone in this; a lot of people are ashamed they killed terrorists. Here [in the group] we can say we did that and we did so honorably.”

Lion says that he is lucky the war did not ruin his life but he thinks he would have had to deal with shame and seek treatment if he had not saved the soldier’s life when the helicopter never came.

Now Lion’s children serve in the army and he does not have the same feeling toward the military that he did when he was younger.

“My mother told me I had to eat to become a soldier. That was my education. … Now, I tell the children they don’t have to go the army,” he said. “And if you go, it’s a very complicated place. It can be good for Israel but it also can be bad,” he said.

His feelings toward the military today are also mixed.

“I think the IDF is better in lots of ways, in equipment and conditions for the soldiers, the way the commanders treat soldiers, it’s better. But their ability to go to war is very low; the army is not working correctly. … We need to make an army of volunteers and only the best will serve,” he said.

Responding to Lion’s claims, the Israel Defense Forces said, “The IDF is prepared for any scenario and always acts with transparency, and in accordance with its values.”

The soldiers’ responses in the Facebook Group are not unique to the Lebanon war.

“Almost a year after, it was difficult for me to sleep. … What helped me after the war was to [keep busy]. … I was working more than what I was supposed to, to not spend any time at home or have a second to myself to think about life,” Matan Zaken, who served in the Golani unit in Gaza in 2014, told The Media Line. “I kept everything inside of me. It took me around three or four years to talk to someone.”

Zaken says he is doing much better now and hopes this will be the year he shares his full story, which he hasn’t told anyone except members of his unit, on Memorial Day. He plans to speak to students in a French-Israeli school in Paris, where he now lives, over Zoom.

“I’ve told myself for three or four years now that I want to tell the story on Memorial Day, but at the last minute, I didn’t want to or it didn’t happen. Maybe this year I will open up.”

With hope, many other soldiers will feel comfortable to share their stories for the first time, as well.