The first time Niloufar Momeni took her hijab off she was in France, on a trip with her family. She describes how amazing the wind going through her hair was, how for the first time she could style her hair, and how free and happy she felt.

Far Avaz did it for the first time while visiting Turkey. She, however, felt fear instead of happiness. She remembers looking around for policemen who might imprison her for removing the head covering; she felt persecuted as if she was still in her homeland.

Both women come from Iran, which forces women to wear hijab whenever they’re outside of their homes. Other countries such as Afghanistan do the same. Still, most Muslim countries’ governments do not oblige women to don the hijab, but in many of these places, conservative families impose it on their post-puberty females.

A recent photo of Niloufar Momeni, Canada. (Courtesy)

“Hijab” in Arabic means “barrier” or “partition.” It is used to refer to the apparel that many Muslim women use to cover their heads in public aiming to maintain modesty under Sharia, Islamic religious law.

There are, however, many variations of such apparel. “Hijab” is used to refer to the concept of covering in general, and to a scarf that covers a woman’s head and hair.

There are also the niqab and the burqa, for example, which additionally cover the woman’s face, with a narrow difference: A niqab has a slit for the eyes, while a burqa has a screen over that opening. These are popular in countries such as Saudi Arabia and Afghanistan, respectively. There are many other styles of such apparel, which can vary based on culture.

On February 1, the ninth annual World Hijab Day will be marked. On this day, women across the globe, Muslim and non-Muslim, are encouraged to wear a hijab. The day started as an initiative to fight Islamophobia. Regardless, many Muslim women expressed discontent with the campaign, saying the custom is imposed on many of them, and should not be celebrated.

The debate continues.

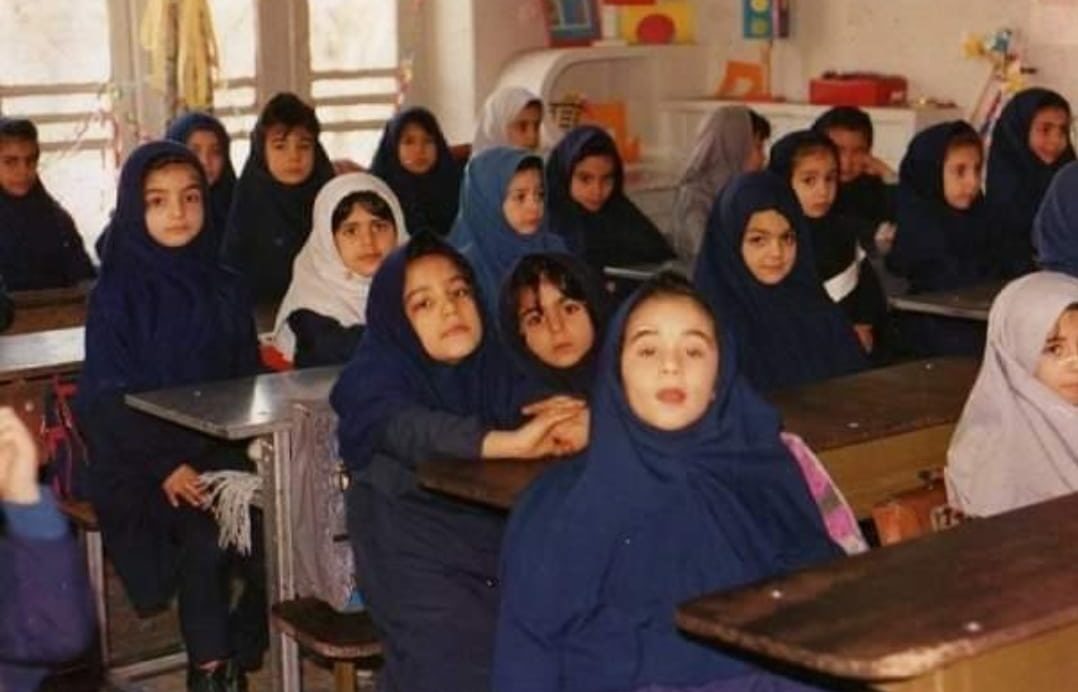

Niloufar Momeni’s first grade class in a Teheran elementary school, 1989. (Courtesy)

In Afghanistan, for example, women are protesting in the streets against the Taliban government’s regulations restricting their rights, including the obligatory wearing of the hijab. There have been mass protests in which some women take off their burqas and burn them in public places as a sign of resistance.

Frontline view of an Afghan woman

In recent weeks a wave of women’s rights demonstrations has been taking place in Afghanistan. Attendance is estimated at between 100 and 200 people, mostly women, a source tells The Media Line.

Asra Stanikzai, a defense lawyer living in Kabul, is one of them. She has been an active participant in these protests even though it could be dangerous for her, and for her loved ones.

Stanikzai explained to The Media Line that most of the women taking part in these demonstrations are just like her. Educated women who lost their jobs, and their positions in society, when the Taliban took over the country last summer. “Most of these women are furious,” she added.

The hijab is part of Afghan culture, important for both the religion and the culture, she said. That is why, she added, “I feel comfortable wearing a hijab in Afghanistan. If I were in Europe or America, the story would be different.”

The problem, Stanikzai said, is that the Taliban wants women to wear the burqa. “We don’t want to cover our faces. The Taliban wants to remove women from society, and this is the first step.”

The Taliban has indeed shown the intention to make the burqa mandatory for all women in the country. The last time the radical Sunni Islamists were in power, in the 1990s, the all-covering burqa was made mandatory in the provinces but not in Kabul. This was possible due to the conservative, tribal way of life of most people in those places. The practice has endured there until now.

In Kabul, on the other hand, women only cover their hair with a headscarf. Nevertheless, the Taliban has lately placed posters at cafés and other public places with the slogan “According to Sharia, Muslim women must wear hijab,” accompanied by the image of a woman with her face covered by a burqa.

A spokesman for the Taliban government’s Ministry for the Propagation of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice, the state agency in charge of implementing Islamic law, said it is just an encouragement for women to follow Sharia. Despite this, plenty of women in Kabul have expressed discontent and participated in the demonstrations.

Stanikzai said that since the Taliban took over, most of the new laws are “against women” and imposed drastic changes on them. “For now, all educated women like me are sitting at home. They can’t go to work; they can’t be educated.”

A lot of these women feel that the Taliban is using the burqa as a mechanism to isolate them from the social order, and that is why some of them took off their burqas and burned them during the demonstrations, she said.

Zaryab Paryani and Tamana Ibrahimi, two women who did just that, were taken away from their homes in the middle of the night by the Taliban, and their location is unknown, Stanikzai said.

She added that Taliban members followed many women to their homes after the demonstrations, including her, and they are expecting severe consequences. That is why many are in hiding.

“Many of our friends disappeared; we do not have any contact with them,” she said. “Women are not taking part in demonstrations anymore, because they fear for their loved ones. So the demonstrations are over for now.”

The Islamists didn’t do anything big against the participants during the actual protests, because there were a lot of women with smartphones filming the scene, Stanikzai said. “The Taliban presents many things to the international media that are not true in order to get accepted by other countries. That is why they are so afraid of our cameras.

“We have many other matters that we should solve, such as poverty and educated people leaving Afghanistan. We don’t have a secure society, but they won’t pay attention to it. They just want to make everything about women. Our hijab is not the important thing that they should worry about,” she said. “Afghan women are careful about what they wear; we don’t need them to guide us regarding Islamic law.

The Taliban tell women who complain: “If you don’t like our laws, you can leave,” she said. But Stanikzai is not ready to give up. “I don’t want to leave Afghanistan so fast; I want to try to stay and fight for my and all Afghan women’s rights.”

Women who took off their hijab

Social media plays a vital role in this controversy. It has seen activism for and against the use of the hijab, including extensive debate about World Hijab Day and No Hijab Day, and the #LetUsTalk and the #DressedNotOppressed campaigns.

Yasmine Mohammed, a Canadian writer and women’s rights activist, shared her story with The Media Line.

Mohammed was raised in a Muslim family in British Columbia and her parents divorced when she was young. Her mother remarried, becoming the second wife to a very religious man who forced Mohammed to wear a hijab from the age of 9. “Everything in my life changed when she let him into our lives.”

Yasmine Mohammed’s first day in an Islamic school, Canada, 1987. (Courtesy)

“When I was 19, I was forced to marry a terrorist who is now jailed in Egypt because he was a member of al-Qaida,” she said. Her mother and stepfather described him as a “strong man” who would be able to control her because she was “not submissive enough.”

Mohammed eventually married; she said her husband was much more severe. “I went from wearing the hijab to wearing the niqab. He even wanted me to cover my hands and ordered gloves from Saudi Arabia.”

She added, “A short time after the marriage, the physical and sexual abuse began.” Then, she said, “I had a daughter with him.”

Having a daughter changed Mohammed’s way of thinking. “It gave me the courage to escape from that world. … I didn’t want her to grow up in, or even remember, the world that I grew up in.”

She added that she wanted to change herself and become a role model before her daughter was old enough to remember “what it looked like to have a mother who was being beaten and then wearing niqab to cover her bruises.”

A recent photo of Yasmine Mohammed, Canada. (Courtesy)

In 2019, Mohammed decided to create “No Hijab Day,” also on February 1 each year. On that day, she asks women to share pictures of them with, and without, hijab together with their personal stories, the reasons for their decisions and the price that they had to pay to put what they want on their own bodies.

This, Mohammed explained, came after she saw the hijab was being presented by what she calls Islamist propaganda as a symbol of freedom. “They don’t even want to acknowledge the fact that women are thrown in prison, getting their faces disfigured, losing their families, friends and communities, and being threatened with death or actually being killed over hijab.”

An Iranian expat’s perspective

Far Avaz is a singer from Iran, a country where her profession is illegal for women. Four years ago, while on a trip to Germany, she learned that an Iranian court had sentenced her to a year in jail for an underground singing performance. Feeling she had no choice, she remained in Germany with only the 22 pounds of belongings she had brought with her, and applied for asylum, knowing she could never return to her homeland.

Singer Far Avaz. (Courtesy)

Avaz told The Media Line she took off the hijab as soon as she could. It feels imprisoning, she explained. “It feels really bad; it feels as if you don’t have control over your own body.”

In Iran, not wearing a hijab is a crime. “We are just forced to wear it; there are police officers standing in the streets checking women’s outfits.” Avaz added that for her, wearing a hijab means being a slave.

Female singers in Iran are often oppressed. (Courtesy Far Avaz)

Iran was a secular country until 1979 when the Islamic Revolution ousted Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. Since then, the Islamic Republic has been ruled by a fundamentalist Shiite cleric, the “supreme leader.”

That changed everything for Iranians, especially for Iranian women, whose lives were heavily affected by the Islamist regime’s new laws and restrictions.

Niloufar Momeni lived in Iran for 16 years and now resides in Canada where she works as a sports journalist, also told The Media Line about being forced to wear a hijab during her childhood.

No woman in Iran is given a choice regarding the hijab, she explained. “They’re forcing their ideology on you.” She added, “It’s not right to force someone to do something for the rest of their life, not by your father, not by your family, and certainly not by the government.”

A Palestinian trapped in her hijab

A Palestinian from the West Bank, who chose to remain anonymous, discussed the issue with The Media Line.

While the Palestinian Authority government is secular and does have a law mandating the hijab, many families take matters into their own hands.

This Palestinian woman said she is compelled by family members to wear a hijab. However, every time she leaves home and feels she is far away enough, she takes it off, regardless of her parents’ wishes.

She said she doesn’t feel religious and enjoys going without the head covering. “I don’t feel comfortable, nor confident [wearing it], because I don’t feel as pretty.”

In addition, wearing it gives people the wrong perception. “When I’m wearing a hijab, people see me as a religious person and expect me to be more religiously observant,” she said.

Many of these women who took off the hijab have things in common. All of them mentioned that the hijab is not comfortable, and it makes them feel hot, or not pretty, or trapped.

“It is very warm; you can’t breathe properly, you feel suffocated,” Momeni said.

“It is a sensory deprivation chamber; all of your senses are blocked. You cannot see, smell, hear or eat properly.… You feel like a ghost walking among people,” Mohammed added.

Having to wear hijab is a perfect rule to demean women on a regular basis

But it does not end there. Most of them think there is something else behind the enforcement of the hijab in certain countries or families. Momeni said the obligatory garment, along with other regulations such as those restricting females’ family and travel rights, are tools of the Iranian regime to demean women. “Having to wear hijab is a perfect rule to demean women on a regular basis.”

Mohammed described the hijab as “gender segregation, a tool of rape culture, anti-women and anti-freedom.”

Avaz thinks it is all about having domination over women. “They want to have control over your mind and body, but they will never manage to control our minds,” she said.

Likewise, these women characterized most of the arguments made to them for wearing the hijab as absurd. They all mentioned the “temptation” that seeing a woman’s hair can cause men.

The hijab in … gender segregation, a tool of rape culture, anti-women and anti-freedom

Mohammed said, “When half of the population is forced to cover themselves in order to not lead the other half into sin, you have a real toxic ideology.”

Avaz added, “Everybody knows that rape doesn’t have anything to do with what you’re wearing.”

As for women who wear the hijab by choice, Avaz suggested they are “brainwashed” when they are children. “They are told: ‘It is dangerous, you will go to hell, you’re a better woman by hiding yourself.’”

Mohammed agrees, saying “choice” is a tricky word. “When you’re given the choice between wearing the hijab or burning in hell for eternity, or your family will disown you.… This is not a free choice.” Nonetheless, she said, “They are entitled to wear the hijab as much as I’m entitled to tell my story.”

Women who wear their hijab by choice

Several women who do wear the hijab shared their positions. Sefat E. Kaniz, from Bangladesh, told The Media Line she wears her hijab by choice and that it doesn’t keep women from doing what they like. “I’m a cycler and a designer. Wearing my hijab and burqa can’t stop it.”

Sefat E. Kaniz. (Courtesy)

Mursal Farotan Khashy, founder and president of For Afghan Women (FAW), fled Afghanistan because of family issues. She told The Media Line, “Hijab is not just a piece of cloth for me.”

Mursal Farotan Khashy. (Courtesy)

Dressing modestly is a choice for her. “I dress myself according to my values and not according to how others want to perceive me.”

Rania Albayaa lives in Cairo. She recently earned a degree in English and has been wearing the hijab for more than 10 years.

Rania Albayaa. (Courtesy)

Albayaa told The Media Line she does so because it is part of her people’s tradition and religion. “We need to cover the parts of our body that may cause temptation.”

She added that the hijab helps to prevent many issues that happen in her society. “In Egypt harassment [of women] is very common, so hijab usually helps us to save our body from any look that we don’t want to see in someone’s eyes or an expression that we don’t want to hear.”

I dress myself according to my values and not according to how others want to perceive me

Mariam Bint Salman Sayed is an entrepreneur and weightlifter from Mumbai, India. Sayed explained to The Media Line why she wears a hijab: “We rationally believe that the creator exists and by default, we as his creation have to follow the creator’s instructions to the best of our ability.” This includes wearing modest clothing, she added.

Entrepreneur Mariam Bint Salman Sayed. (Courtesy)

Albayaa said the hijab “saves you, the woman you are, your body, your insecurities.”

Kaniz said it “is a personal choice to wear or not a hijab.”

Moreover, Sayed believes that women who advocate for hijab-wearing are “brand ambassadors” of Islam.

Khashy added, “If I choose not to wear my scarf, I don’t want to be celebrated, and if I chose to wear it, I don’t want to be judged for it.”

Should governments intervene?

Most of the women who spoke to The Media Line feel that governments should not get involved in what women wear.

“We must stop imposing [rules] on women’s clothing,” Khashy said.

Albayaa said, “Hijab is something that you decide on your own. In our religion, we are not supposed to force anyone to do something.”

Likewise, some of them expressed disgust with institutions that do forbid the wearing of the hijab.

Sayed said governments and institutions that do not allow women to wear the hijab are violating freedom of expression and “it is a strong indicator of Islamophobia.” Forbidding women to wear clothing of their choice constitutes “disregard of their intellect and ability to think,” she said.

We should stop labeling women. Every woman is perfect regardless of her age, skin color, weight and choice of clothing

Khashy wants a world where “difference of opinions and values are respected.

She added, “We should stop labeling women. Every woman is perfect regardless of her age, skin color, weight and choice of clothing.”

For some, the hijab represents a living hell, oppression, lack of freedom, and a tool used to degrade women. For others, it is a way to express themselves, to serve the creator, and to be an ambassador of their religion and culture. For some, it is suffocating, while for others, it is liberating.

But all the women we spoke with agreed that every woman is entitled to have a choice. For both sides, the power to choose whether to wear the hijab is a symbol of women’s empowerment. “We are intelligent, so let the women do whatever they want,” Stanikzai said.