Indian PM’s Visit to Ukraine: Historic Act or Empty Gesture?

The visit is part of an attempt to communicate India’s multivector foreign policy, a stance that has significant implications for India’s relationship with the Middle East

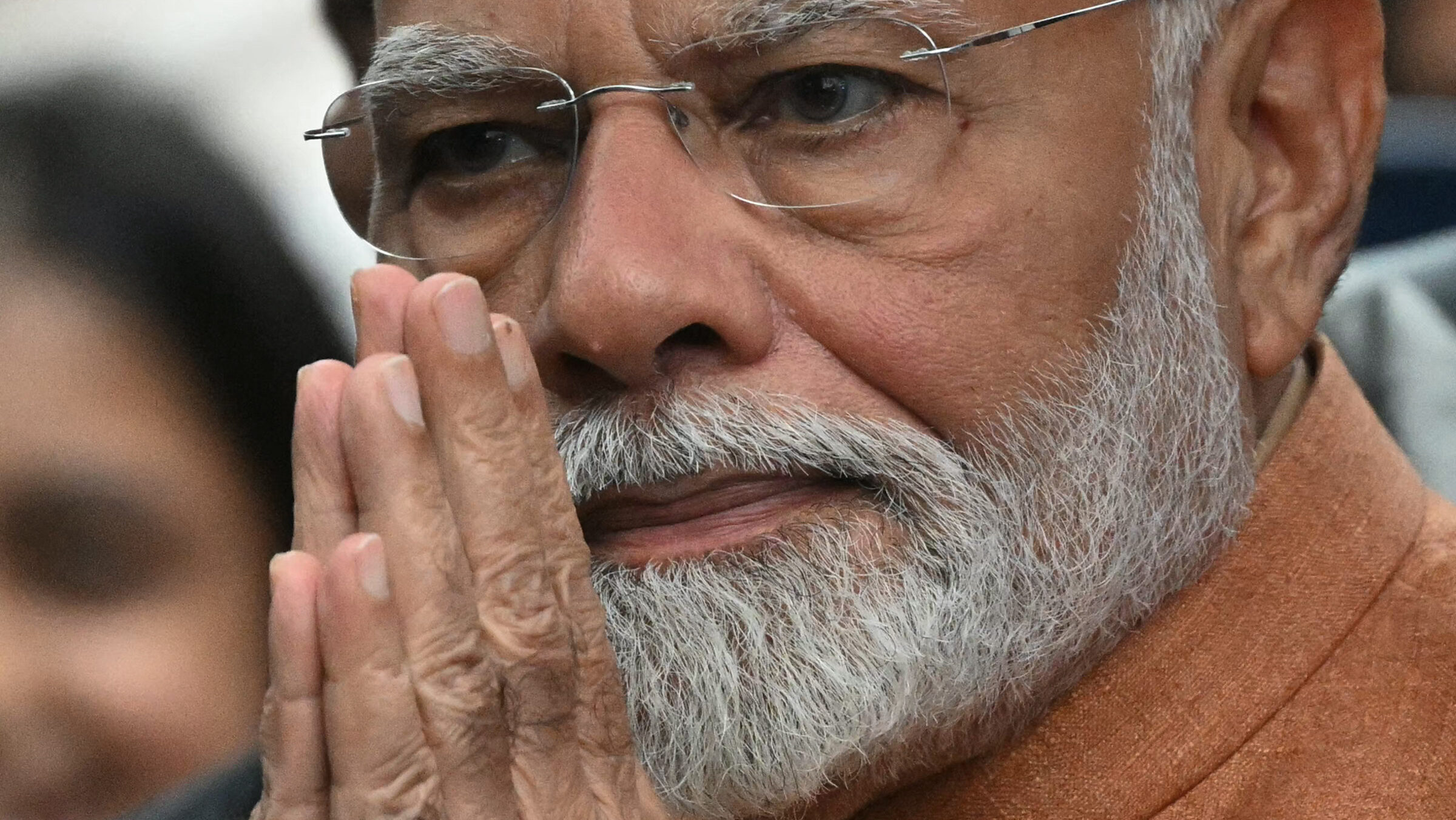

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to Ukraine on Friday is a historic event, marking the first visit of an Indian prime minister to the country since Ukraine gained independence from the Soviet Union in 1991. This visit follows Modi’s recent trip to Russia, where he met with President Vladimir Putin and reiterated India’s call for a peaceful resolution to the ongoing conflict in Ukraine.

These visits are strategically significant for India’s relations with Ukraine and Russia and the country’s diplomatic and strategic interests in the Middle East. India has strong economic ties with Middle Eastern countries, where millions of Indian expatriates also live, making it all the more likely that countries in the region will closely note India’s balance of relationships with major global powers.

Amitabh Singh, a professor at Jawaharlal Nehru University’s Center for Russian and Central Asian Studies, told The Media Line that Modi’s visits are meant to send a message both domestically and internationally.

Domestically, Modi intends to communicate to his constituents that he is pro-peace, Singh said. Internationally, he said, “he aims to address the Global South, sending the message that India is not solely aligned with the USA but maintains a balanced relationship with Russia as well. This effort is directed toward facilitating a fair dialogue between both sides to achieve peace in the region.”

Ukrainians have mixed feelings regarding Modi’s visit.

Ukrainian diplomacy is performing wonders by engaging with all sides, so the Indian prime minister’s visit will be welcomed at the highest level, bringing happiness and health, as we say in Ukraine. However, there is some resentment toward India, especially due to its purchase of Russian energy resources. During a major war, the world becomes black and white, and different nuances hold little interest for the broader public.

“Ukrainian diplomacy is performing wonders by engaging with all sides, so the Indian prime minister’s visit will be welcomed at the highest level, bringing happiness and health, as we say in Ukraine,” Ukrainian media analyst and political consultant Oleksiy Kovzhun told The Media Line. “However, there is some resentment toward India, especially due to its purchase of Russian energy resources. During a major war, the world becomes black and white, and different nuances hold little interest for the broader public.”

He said that India’s decision to buy cheap Russian energy is understandable, given its attempts to lift much of its vast population out of poverty. Given India’s status as a nuclear power, Kovzhun predicted that Modi and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy would discuss food security and nuclear safety.

Give the gift of hope

We practice what we preach:

accurate, fearless journalism. But we can't do it alone.

- On the ground in Gaza, Syria, Israel, Egypt, Pakistan, and more

- Our program trained more than 100 journalists

- Calling out fake news and reporting real facts

- On the ground in Gaza, Syria, Israel, Egypt, Pakistan, and more

- Our program trained more than 100 journalists

- Calling out fake news and reporting real facts

Join us.

Support The Media Line. Save democracy.

“We might see some symbolic gestures, such as humanitarian aid—something small but significant, demonstrating goodwill,” he said.

Singh said that the visits are meant purely as an expression of Modi’s desire for peace between Russia and Ukraine.

“By engaging with both Kyiv and Moscow, alongside leaders like those from South Africa and Hungary, he is telling the world that India is deeply concerned about the violation of Ukraine’s boundaries,” Singh said. “Though neutrality between both camps has had its challenges, he is striving to project India as a peacebuilder—a legacy he wishes to leave behind.”

In India, Singh said, people see the conflict in Ukraine as a proxy war between Russia and the West, specifically the US and NATO.

During a major war, the world becomes black and white, and different nuances hold little interest for the broader public.

“However, there is some resentment toward India, especially due to its purchase of Russian energy resources. During a major war, the world becomes black and white, and different nuances hold little interest for the broader public,” he explained. “Additionally, the West’s moral high ground in advocating for a rules-based international order is being questioned, particularly in light of their actions in Israel and Gaza. The inconsistency in their stance is evident when they condemn bombings in one context but seem to turn a blind eye in another, causing the West’s moral authority to take a beating in the Global South.”

Kovzhun expressed criticism of India’s blanket pro-peace stance, which he described as naive.

Ukrainians, hardened and exhausted from war, understand that simply saying ‘this needs to stop’ doesn’t work.

“It’s like with German students: ‘War is bad, peace is good. When people kill each other, it’s terrible, and we should make sure it doesn’t happen.’ This sounds great when you’re 15 years old, but from state leaders, it sounds strange. Their motivation is clear: ‘Please stop upsetting my voters; they watch TV, and their moods are ruined,’” Kovzhun said. “Ukrainians, hardened and exhausted from war, understand that simply saying ‘this needs to stop’ doesn’t work.”

For that reason, he said, Ukraine became a leading supporter of Israel after October 7, even as other countries criticized Israel for its harsh response. Ukrainians understand “all too well what a sudden attack and a monstrous eruption of violence mean,” he said.

According to Singh, India is one such country deeply concerned about the civilian casualty toll in Gaza.

“While we do not support Hamas or its actions, including the October 7 attack, we are troubled by the excessive force used by Israel, leading to a humanitarian crisis. The public perception is that Israel is going overboard, and this does not align with the rules-based international order that the West advocates,” he said.

Singh said that India is highly interested in keeping strong ties with countries in the Middle East, especially because of the 9 million or so Indians working in Gulf countries like UAE, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia.

“These workers send approximately $100 billion back home in remittances, and India is also one of the largest oil markets for these countries,” he said. “Given this, we do not want to disrupt our relationship with the Middle East, which is vital to our economic interests.”