Inside the War Zone: Galilee Medical Center Prepares for Conflict With Hezbollah

The Nahariya hospital moves its critical units underground to ensure patient safety during increased tensions.

Dr. Uriel Trahtemberg, head of the General Intensive Care Unit (ICU) at Galilee Medical Center, keeps a change of clothes and some underwear in his office. He and his wife, a teacher, have planned for a significant escalation between Israel and Hezbollah. If it happens, Trahtemberg will sleep on his office couch and shower at the Nahariya hospital while his wife will leave the city with their children.

Since October 8, the day after Hamas infiltrated Israel and killed 1,200 people, Hezbollah has been firing rockets across the Lebanon-Israel border. Over 5,000 rockets and missiles have been launched so far, according to the Israel Defense Forces (IDF). Despite diplomatic efforts, there is an understanding that the situation will likely worsen before it gets better.

“My concern is when the war is coming and when the intensive work is coming, will I be able to get all the doctors and nurses to the hospital?” asked Prof. Masad Barhoum, the medical center’s CEO. “I ask myself, ‘What if they won’t be able to reach the hospital?’”

My concern is when the war is coming and when the intensive work is coming, will I be able to get all the doctors and nurses to the hospital?

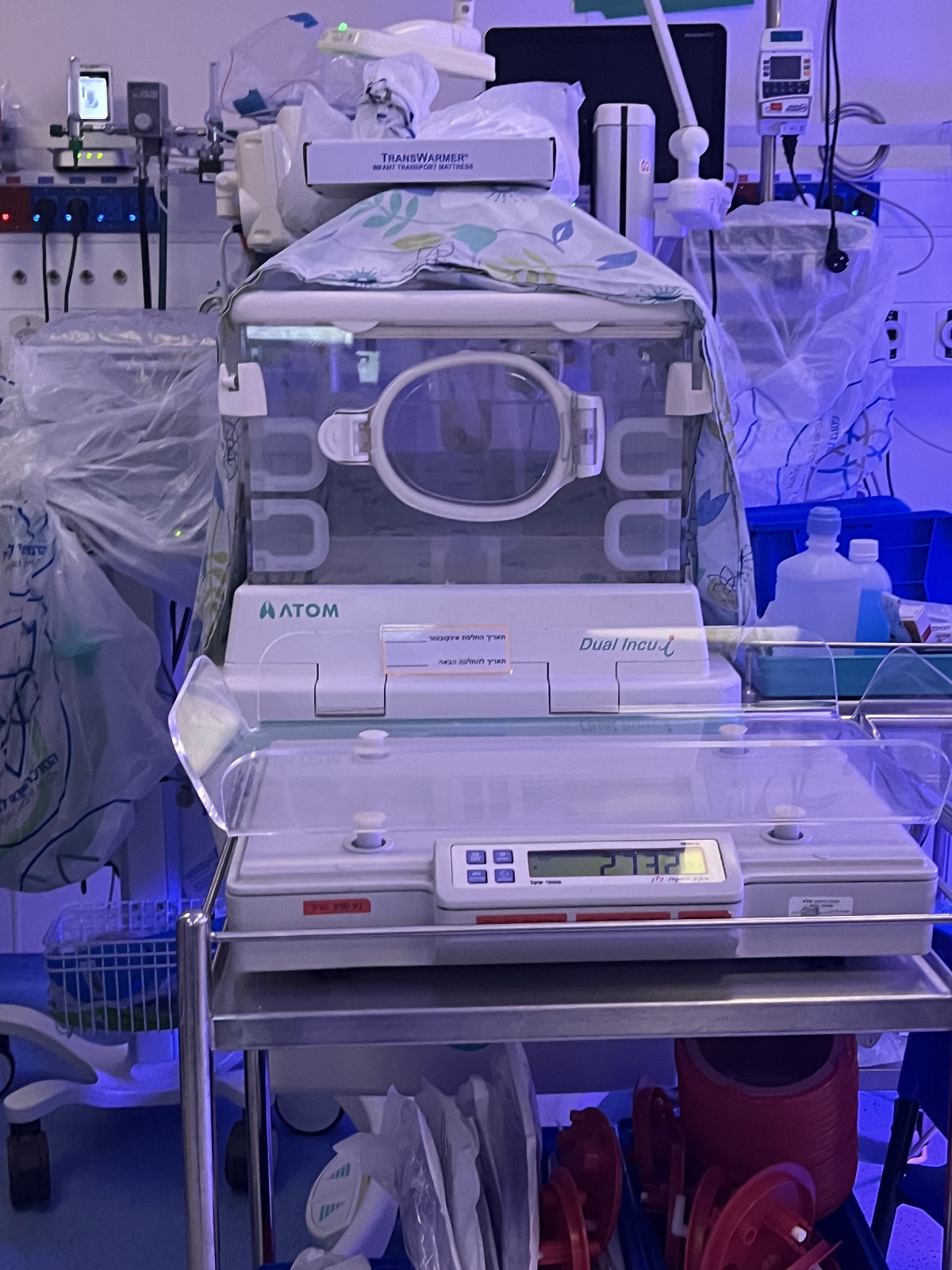

Galilee Medical Center, located less than 10 kilometers from the border and the only trauma center for 40 kilometers, has already been operating in war mode. On the day of the Hamas attack, the leadership anticipated the likely escalation on the northern front. Within five hours, the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU), the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU), the Intensive Care Unit, and the central laboratories were all moved to the underground, protected emergency complex. The birthing center is reinforced above ground.

“This is a significant operation involving incubators and respirators,” explained NICU Director Dr. Vered Fleisher Sheffer. “It is not simply carrying babies downstairs.”

The senior management and staff at Galilee Medical Center have prepared for what some say is now an inevitable war for nearly nine months. Barhoum acknowledged that no hospital could be fully prepared for an event like October 7 but said, “We are prepared for a mass casualty event.” The staff has been “working for more than eight months underground. I will not say that they are pleased [about it]. But I didn’t have to work too much to convince them that this is how we have to work. … They are very convinced that this is what we must do to protect them, the employees, and the patients.”

When a siren blares, Nahariya residents have only 15 seconds to reach shelter. In some cases, there is no warning.

Galilee Medical Center is the primary receiving hospital for casualties in the north, serving civilians and military personnel. To prevent the hospital from being overwhelmed, patients evacuated by medical helicopter are taken 10 minutes further to Rambam Medical Center in Haifa. However, most patients arrive by land and are treated at Galilee Medical Center.

“Part of the lessons learned from the south—and we have performed a couple of drills about it—is to become a triage hospital,” explained Trahtemberg. “If war breaks out and there are a lot of military and civilian casualties and trauma—if a missile or rocket falls on an urban area, you have 20% of moderate and severe cases, but 80% of people need medical care that isn’t an immediate threat to their life. That [80%] is what overwhelms a system. So, we will become a triage hospital. Those in immediate danger, we admit, and those that don’t need immediate care, we move further south.”

So far, hundreds of war casualties have arrived at the hospital from various settlements on the northern front, including dozens in critical condition. Some casualties were civilians injured by missiles or mortars coming from places like Shtula, Arab al-Aramshe, Hurfeish, and more.

For example, 11 patients arrived from a mortar attack at a soccer field in Hurfeish earlier this month, one of whom was pronounced dead upon arrival. In another instance last month, a UAV laden with explosives flew into a room at an army base, injuring 22 soldiers. Of those, one was dead on arrival, three were transferred directly to the ICU, two needed immediate surgery, and the rest did not require critical care.

“That’s the usual distribution of injuries in military trauma,” Trahtemberg said.

To accommodate the influx of patients, Galilee Medical Center opened a second trauma room, also located underground. However, as of now, most of the severely wounded have since been transferred to rehabilitation centers, such as Sheba Medical Center near Tel Aviv.

Hospital Underground: Conditions Are Difficult

Trahtemberg said that day-to-day operations at Galilee Medical Center have been “severely disrupted” from a logistical perspective. Usually, the hospital has 800 beds, but that number is halved when operating in the underground facility. Despite some 60,000 northern Israeli residents evacuating their homes, the hospital’s catchment area has not changed. Many evacuees from areas like Safed and Poriya have moved closer to Nahariya or Tiberias.

Give the gift of hope

We practice what we preach:

accurate, fearless journalism. But we can't do it alone.

- On the ground in Gaza, Syria, Israel, Egypt, Pakistan, and more

- Our program trained more than 100 journalists

- Calling out fake news and reporting real facts

- On the ground in Gaza, Syria, Israel, Egypt, Pakistan, and more

- Our program trained more than 100 journalists

- Calling out fake news and reporting real facts

Join us.

Support The Media Line. Save democracy.

The hospital sometimes sees 10 critical care admissions in a single day, compared to an average of 4.5 at regular times, he notes. Most days, the number of admissions is at least double the usual rate.

Trahtemberg said the underground ICU was crowded, had less privacy, and had limited capacity to perform bedside procedures or manage worsening patients.

“The medical care hasn’t worsened,” Trahtemberg stressed. “But the conditions are much more difficult.”

The ICU team was understaffed even before the war. Trahtemberg said his team includes five staff physicians, three critical care fellows, and three to five rotating residents. Recruiting critical care physicians is challenging worldwide, both in Israel and elsewhere. In the Western and Upper Galilee, Israel’s periphery, it’s tough because doctors are reluctant to relocate there.

“We do not have anyone to fill the roles,” Trahtemberg admitted.

Working at the center is fraught with constant stress for the staff, who must always be prepared to respond swiftly to alarms and disruptions, Trahtemberg added. He described the challenges of navigating daily life amidst frequent alerts and the uncertainty they bring, often requiring staff to wait anxiously in shelters for updates in the middle of treating a patient. This environment disrupts workflow and affects those involved’ mental and emotional well-being.

We are the unit that handles the most critical and complex cases

“We are the unit that handles the most critical and complex cases,” he explained, highlighting the high demands and pressures health care professionals face in critical care, a field already prone to burnout.

The logistical difficulties, compounded by personal concerns, such as family members in the military or affected by local hostilities, further strain their ability to maintain the expected level of performance. Despite these challenges, Trahtemberg stressed that the staff’s dedication remains unwavering.

“At a human and personal level, you cannot ignore that people deliver health care,” he said.

“What worries me is what happens if a rocket hits the hospital and we cannot provide care?” Trahtemberg added. “Imagine that half a building collapsed. Being faced with the possibility of there being an acute and dire need for care and not being able to provide it—that, for me, would be horrible.”

Finally, Trahtemberg said there is “a list of at least 10 things that are just on hold or waiting to be introduced in the hospital for nine months—new technologies, protocols, academic initiatives.”

‘We Can Keep Them Safe’

A short set of winding stairs leads to the underground NICU in a nearby building. It’s warm and dark, yet somehow unsettling. Incubators line the walls, each holding a fragile baby. The space is compact, reminiscent of the adult ICU.

“There is a lot less room here,” acknowledged Director Sheffer. “We can accommodate 18 babies now, compared to 37” in the pre-war unit.

Naturally, fewer women are giving birth at Galilee. Most prefer to travel further for more standard facilities if they have a choice.

“Those who still choose to give birth here are people who know us and trust that we can keep them safe,” Sheffer said. “The conditions are not typical; ordinarily, every woman would have her room. Today, that’s not the case. Some prefer more comfortable surroundings, which I cannot currently provide. However, our medical care remains unchanged; war does not justify compromising quality.”

Sheffer said the main challenge arose from the broader national context, where individuals struggle to escape the pervasive impact of ongoing events, even within the confines of their homes. Many families have been displaced, compounding the initial hardships.

She said another significant issue was prolonged confinement underground, in spaces devoid of natural light.

Finally, communication among people was strained.

“Finding more effective communication strategies under these stressful conditions is paramount,” Sheffer said.

The hospital has stocked up with two weeks’ worth of supplies in case of an escalation, and drills have been performed. Both Sheffer and Trahtemberg said there was some fear, but for the most part, “over the last nine months, we have become more cohesive and more determined in getting ready, so when the time comes, we will be able to do this,” Trahtemberg said.

He added that the war had also highlighted the ability for Arabs and Jews to work together under fire. According to the Central Bureau of Statistics, around 55% of Israel’s Arab population lives in the north of the country.

“The war has highlighted that we share a destiny,” Trahtemberg said. “In the first weeks, things were a bit tense. But something happened—I think the realization that the enemy is not Arabs or Jews but extreme, radical ideology.

“Christians, Muslims, Druze, Jews—we can coexist,” he continued. “This hospital is living proof.”

Trahtemberg said that he believed that any conflict with Hezbollah, unlike the nearly nine months spent in Gaza, would likely last no more than two to three weeks, though likely involving heavy artillery and significant casualties. He and Sheffer expressed hope that once any escalation concluded, it would pave the way for more peaceful times.

When I treat a patient, their name or origin is irrelevant; I provide the best care possible

“When I treat a patient, their name or origin is irrelevant; I provide the best care possible,” Sheffer said. “I believe in peace and aspire for it. Maybe, one day, we can coexist peacefully.”