After October 7, Can Jewish-Arab Trust in Israel Be Rebuilt?

Since the October 7 Hamas attack, many Israelis, including residents of mixed cities, feel heightened distrust and anxiety towards Arab Israelis. Social media and past conflicts exacerbate these tensions, impacting daily life and Jewish-Ara

Since the October 7 Hamas massacre, Trevor Fletcher’s life has been filled with suspicion and unease.

Relocated from Kibbutz Sufa to Ramat Gan after the attack, Fletcher said he is wary of local Arab Israeli bus drivers or doctors. Although he acknowledged that not all Arabs are adversaries, the uncertainty about who to trust is deeply unsettling.

“I hear conversations in Arabic about ‘Palestine’ and can’t help but worry about their intentions,” Fletcher told The Media Line. “What could they be talking about? To me, they are a danger. These are the guys who could carry out the next attack.”

Fletcher is particularly concerned about the potential for another eruption of violence, especially within mixed Arab-Jewish cities, and fears that Arab Israeli citizens might turn against Jewish citizens.

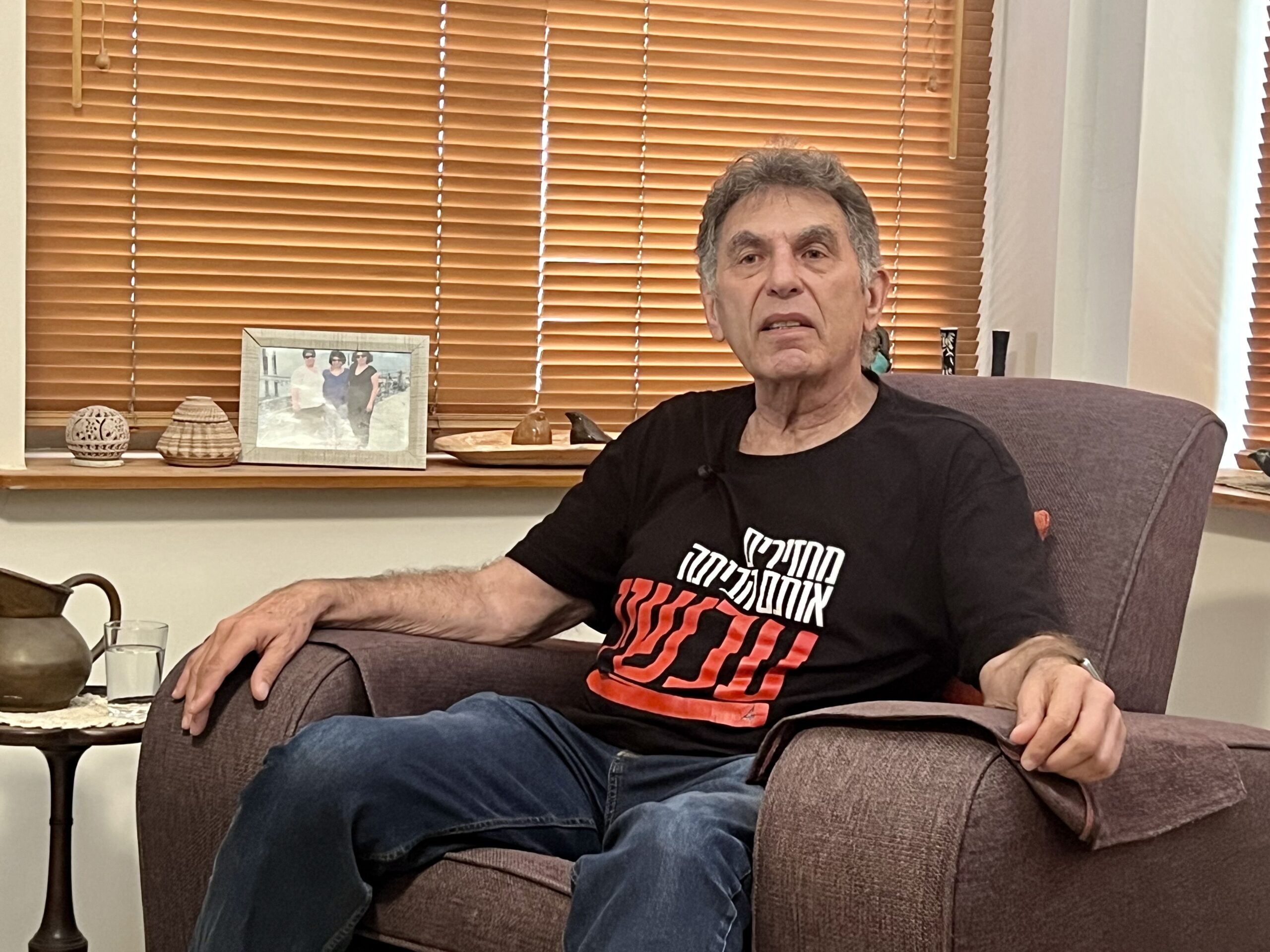

Trevor Fletcher in his Kibbutz Sufa home (Credit: Maayan Hoffman)

Social media has exacerbated his anxiety. He said he frequently encounters disturbing posts from Arabs in Jerusalem and nearby areas, expressing desires for a repeat of the October 7 attacks. This constant exposure to hostile messages heightens his sense of foreboding.

“Before October 7, I knew something was going to happen,” Fletcher said. “I knew something was coming down, but my mind could not have imagined what happened. So, now, I am suspicious of Arab Israelis living here.”

Fletcher’s heightened alertness is now a permanent state. He is constantly vigilant, scrutinizing his surroundings more than ever before. The pervasive suspicion affects his health as he grapples with the dilemma of identifying potential threats among those he encounters daily. He said the sense of danger is ever-present, altering his perception and interactions in a country where he previously felt secure.

Trevor Fletcher and his wife, Naomi, in their Kibbutz Sufa home (Credit: Maayan Hoffman)

“You hear Arabic, and it just does not go down anymore,” Fletcher said.

Even before October 7, tensions between Jews and Arabs were heightened due to the aftermath of the May 2021 Gaza conflict, which sparked dangerous riots inside Israel’s mixed cities. For some, like Fletcher, the events of October 7 intensified fears and wariness toward Arab neighbors. However, this fear does not appear to be universal. Surveys and ongoing coexistence efforts suggest a hopeful outlook for the post-war future.

‘Trust Must Be Rebuilt’

According to the Israel Democracy Institute, between 2018 and 2020, the most significant tensions in Israeli society were between the Right and Left political camps. However, since the summer of 2021, the strongest tension has shifted between Jews and Arabs, with 45% of people agreeing in the 2022 Israel Democracy Index survey that this is the most intense division.

Multi-year averages shared by the institute show the highest tensions were between Jews and Arabs at 42.8%, followed by Right and Left at 27.7%, religious and secular at 14.3%, rich and poor at 7.5%, and Ashkenazim and Mizrahim at 2.8%. From 2018 to 2022, there was a sharp increase in the percentage of both Jews and Arabs who view relations between the two groups as bad or very bad—rising from 27% to 60% among Jews and from 26% to 45% among Arabs.

Strikingly, following the war, the latest Democracy Index revealed a shift in the primary source of tension in Israeli society. According to Jewish respondents, at the end of 2023, the most significant tension was between the Right and the Left, likely a residual effect of 10 months of judicial reform protests. Tensions between Jews and Arabs, which had been the highest in 2021 and 2022, dropped to second place, accounting for 31.5% of reported tensions.

A separate survey released in March by the Abraham Initiatives organization looked at relations between Jewish and Arab employees five months into the war. It revealed that more than a third (34%) of Jewish employees claimed that their opinions towards Arab employees have worsened. Moreover, approximately 15% of employees, both Arabs and Jews, reported experiencing significant tension at work, such as arguments or anger.

However, the overall trend was positive. Despite rising tensions, 83% of Arab employees and 72% of Jewish employees reported that relations between Arabs and Jews in their workplace were good or very good. While many employees reported that they tend to avoid discussing the October 7 massacre and the war—60% of Arab employees and 48% of Jewish employees have steered clear of these topics—those who did engage in such discussions mostly found them to be positive or neutral (86% of Arabs and 79% of Jews).

The Afkar Institute carried out the survey, which included responses from 660 Jewish and 607 Arab employees working in mixed companies and organizations across various sectors, such as trade and industry, health, transportation, high-tech, and public services.

This holiday season, give to:

Truth and understanding

The Media Line's intrepid correspondents are in Israel, Gaza, Lebanon, Syria and Pakistan providing first-person reporting.

They all said they cover it.

We see it.

We report with just one agenda: the truth.

Abraham Initiatives Co-Executive Director Shahira Shalaby told The Media Line that, unlike the unrest seen in 2021, there has been no significant internal turmoil in Israel since the latest Gaza war began. She attributed this to three main reasons: First, the Arab community understands the sensitivity of the events of October 7 and recognizes that the Jewish community has little tolerance for protests at this time.

Secondly, the Arab community has developed empathy for the Jewish suffering resulting from the attack. Thirdly, the Israeli police have intimidated the Arab community. Shalaby explained that the police warned that anyone protesting or speaking out against Israel could face arrest or worse. She noted that individuals who posted nationalist content on social media have been arrested, with the police sharing their photos online as a deterrent to others.

Jewish-Arab relationships will need to recover, and trust must be rebuilt after October 7. But today, eight months later, we can say that we continued to work and live together despite the crisis. The fact that violence did not erupt within Israel means we can build better relations in the future.

While she has concerns about the police curtailing freedom of speech, she said that eight months into the war, the fact that the situation in Israel has remained quiet despite tensions would “positively impact our collective future” when the war ends.

“Jewish-Arab relationships will need to recover, and trust must be rebuilt after October 7,” Shalaby admitted. “But today, eight months later, we can say that we continued to work and live together despite the crisis. The fact that violence did not erupt within Israel means we can build better relations in the future.

“We could have destroyed [the situation], but we decided not to – both sides.”

Ola Najami, director of the Jewish-Arab Center for Peace, expressed similar sentiments. She said that “after October 7, the Arab community in Israel found itself tested for loyalty both to Israeli society and the Palestinian people.”

At the onset of the crisis, the center promptly took action to prevent flare-ups and escalations between the two communities. At one point, there were calls to fire Arab healthcare workers, Najami recalled. However, it soon became apparent that Arabs make up about 40% of the healthcare system.

Healthcare services in Israel are a very good example of full partnership. We saw how Arabs and Jews fought together in the healthcare system during COVID-19 and now again.

“Healthcare services in Israel are a very good example of full partnership,” Najami said. “We saw how Arabs and Jews fought together in the healthcare system during COVID-19 and now again.”

She said that a sense of frustration, fear, insecurity, and distrust between the two communities was particularly prominent after October 7.

“A sense of insecurity exists in both communities,” Najami said. “The Arab society experiences silencing and intimidation, waves of arrests, students summoned for hearings and suspended from studies due to social media statements. Freedom of expression for all citizens has been compromised, especially for the Arab community.

“It will take some time, but eventually, we will slowly return to normalcy.”

‘I was not ready for October 7’

That is Arnon Avni’s hope.

A resident of Kibbutz Nirim, where five civilians were murdered by Hamas on October 7, with many more injured and some taken hostage, Avni refuses to believe that the Palestinians who worked on his kibbutz shared inside information that aided Hamas’s attack.

Arnon Avni of Kibbutz Nirim (Credit: Maayan Hoffman)

“I don’t blame them,” he said of the Palestinian civilians. He used to go to the border and pick up Gazans and bring them into Israel for medical treatments. “These stories [of Arab spies] are not interesting. They’re trying to provoke us [against the Arabs]. It’s a conspiracy.”

Avni mentioned that Hamas could have gathered all the necessary information from Google Maps. However, he admitted the need to hold on to hope. His more profound concern is how he can continue living in his kibbutz, just 2 kilometers from the border if he fears the people on the other side.

David “Dudu” Pe’er from Kibbutz Mefalsim on the Gaza border is also struggling. A self-proclaimed “leftist who still believes there is a chance for peace,” Pe’er told The Media Line the story of a man named Jamil from Gaza, who started working on the kibbutz when he was a teenager, helping out and doing various tasks. Later, he studied electricity and worked in the kibbutz for many years.

David “Dudu” Pe’er from Kibbutz Mefalsim (Credit: Maayan Hoffman)

During the years when Jamil wasn’t allowed out of Gaza, electricity was scarce, with Israel supplying Gaza only a few hours of power each day. The kibbutz members organized and bought him a solar system for his house. When the borders reopened, he returned to Mefalsim.

“We trusted him completely—I, along with others, would give him the keys to our apartments so he could work while we were away,” Pe’er recalled. “When his daughter married, many of us contributed money toward a wedding gift.”

Jamil returned to Gaza on October 6. After the attack, when people talked about how much information the terrorists had, many accused Jamil of sharing details since he knew everything about the kibbutz. Despite this, Pe’er believes that if he had done so, he would have been forced to talk and not volunteer the information.

Jamil was killed in Gaza in February. The kibbutz learned about it from his son’s Facebook.

“He was like a brother to me, and everyone here liked and respected him,” Pe’er said. “Some even loved him.”

But when asked if he could ever form such a close relationship with an Arab worker from inside or outside Israel again, Pe’er sighed. “I guess so,” he said, “even though there would be some kind of basic mistrust.”

Larry Butler from Nir Oz, one of the hardest hit kibbutzim, said he has applied for a gun license.

“I really don’t trust the Arabs,” he told the Media Line. “I cannot trust them.”

He said he barely leaves his new, temporary home in Karmei Gat except to go back and visit his destroyed kibbutz. Butler’s home was burned down, and all of his possessions were lost. His son was shot in the back.

Larry Butler of Nir Oz (Credit: Courtesy of Larry Butler)

“I was not ready for October 7, but now I am prepared for it,” he concluded. “I used to trust. Now, I don’t trust. When you don’t trust, you are ready for it.”

Fletcher’s son was getting married the week he spoke to The Media Line. He said his wife was suffering from shingles due to the stress she had endured since October 7. He, too, was struggling on what should have been a happy occasion.

“I always knew there were people who wanted our destruction. But I believed that most Palestinians looked forward to a peaceful relationship and learning to live together with the Jews,” Fletcher said. “Before October 7, I saw an opportunity for peace. I don’t think so anymore.”

Still, Fletcher said he hoped to learn to live in Israel with his Arab neighbors in his new reality.