Bearing Witness, Photojournalist Chen G. Schimmel Defies Oct. 7 Deniers

Schimmel: ‘If there aren’t people who are brave and willing to do this, then you don’t have documentation of the events of the world’

The experiences and emotions of October 7, 2023, may still be fresh, but how the day will be described and remembered depends largely on testimonies and images. Photojournalist Chen G. Schimmel set out to capture photographs that tell the story—its grief, courage, and human cost. Her images became a book, a testament to bearing witness and ensuring that the events of October 7 are never erased or denied. In my interview with Schimmel, we discussed what compelled her to take this journey, how it reshaped her view of the world, and why photography can tell these stories in ways no other medium can.

She explained why she was compelled to pick up her camera and head to the sites of the October 7 attacks—places still reeling from unimaginable horror. Her new book, October 7th, Bearing Witness, filled with stark and evocative images, offers a view few others captured in those first chaotic days and in the aftermath of the tragedy.

Schimmel told me she and her family were in Jerusalem that morning when the sirens began. “We all ran to the shelter,” she recalled. Her younger brother, newly drafted into the army, ran to grab his phone. “He came back pale and said, ‘Dead soldiers’ bodies everywhere.’” At that point, she said, no one fully understood what was unfolding. “The country was in shock. Everyone was trying to figure out how to help.”

Each member of her family found a way. “My mother helped wounded soldiers, my brothers collected clothing for evacuees from abroad, and my father volunteered with ZAKA,” she said, referring to the emergency organization responsible for recovering and preparing the dead for burial according to Jewish law. “It’s not just about finding body parts,” she explained. “They clean every last drop of blood to ensure a dignified burial.”

Workers search for remains following the October 7 attack. (Courtesy Chen Schimmel)

When her father returned from his first mission, Schimmel told The Media Line she could see the toll it had taken. “There was a blankness in his eyes,” she told me. “He’d seen something no one should ever have to see.” That moment became her turning point. “I told him that next time, I wanted to go and document it. I knew this was our history being written, and I wanted to make sure it would never be forgotten.”

Getting to the south was no simple task. “Everything was blocked off, the roads were closed, and rockets were still falling,” she said. “You couldn’t go without a helmet and vest—and there weren’t any left, since every reservist and journalist was trying to get one.” It took about a week before she could join ZAKA. “Eight days later, I finally made it down there,” she said. “That’s when my work began.”

I asked what went through her mind as she photographed the aftermath—what moments she knew she had to capture, no matter what.

ZAKA workers at a kibbutz after the October 7 attack. (Courtesy Chen Schimmel)

“It’s hard to explain,” she said after a pause. “The first thing that stays with me is the smell. It’s something you can’t capture and can’t describe. I wanted somehow to photograph what that smell felt like—the silence, the emptiness, the weight of being there.”

She spoke of homes reduced to ashes, of children’s toys and storybooks stained with blood, of a landscape that seemed both frozen and destroyed. “I wanted to document the darkness, the devastation,” she said quietly. “That silence said everything.”

I asked if there was one photograph that could prove to the world that October 7 happened. “That’s a good question,” she said, turning to the pages of her book. “There are two that I always come back to.”

The first was part of a series she titled Hammer. It came from her earliest trip south with the ZAKA volunteers. “We entered a house where an elderly man had been beaten to death with a hammer,” she explained. “Most of the homes had bullet holes or RPG damage, but this one didn’t. Just that hammer, lying there.”

In her photographs, ZAKA workers can be seen carefully cleaning the small wooden handle and metal head. “It’s an object meant to build,” she said, “but here it became a weapon. We spent hours brushing the last traces of blood from the corners with toothbrushes—every bit had to be buried with dignity.”

Give the gift of hope

We practice what we preach:

accurate, fearless journalism. But we can't do it alone.

- On the ground in Gaza, Syria, Israel, Egypt, Pakistan, and more

- Our program trained more than 100 journalists

- Calling out fake news and reporting real facts

- On the ground in Gaza, Syria, Israel, Egypt, Pakistan, and more

- Our program trained more than 100 journalists

- Calling out fake news and reporting real facts

Join us.

Support The Media Line. Save democracy.

Another image, she told me, has never left her. “It was taken in Kibbutz Be’eri,” she said. “A family of seven had been taken hostage through their window. When their relatives came back to the ruins, they searched through the ashes and found a piece of metal buried in the debris. When they brushed it off, it was a menorah.”

That discovery came just weeks before Hanukkah. “I returned on the last night and lit candles with them,” Schimmel said. “That photograph captures what this book is about—the darkness and the light, the pain and the resilience.”

Regarding the family members who were captured, Schimmel added, “It’s amazing to say that since the seven have returned to Israel.” She revealed which scenes had the greatest impact on her as a photojournalist.

“It’s not the same thing as writing,” she said. “You’re seeing it with color. You’re seeing it through black and white. You’re seeing it through the objects that you’re trying to sift through.”

A woman plays piano in a kibbutz after the Oct. 7 massacre. (Courtesy Chen Schimmel)

She said the funerals were among the hardest moments to capture. “I photographed and documented countless funerals,” she said. “For me, funerals are probably the most difficult. At funerals, something you cannot document is the wailing sounds. It’s the pain in the families’ voices.”

Since Schimmel is in her early 20s, I wondered about the impact of witnessing so many funerals. “Before October 7, I had only been to one funeral—my grandfather’s,” she said. “Usually, we go to the funerals of those we’re very close to or family members. This felt similar and different, because they are our soldiers and our brothers in arms.”

We talked about her time in Hostages Square, where she has spent the past two years photographing and speaking with families. “Yes,” she said. “And I think it’s the resilience. Through all the sadness and the devastation, it’s truly the resilience.”

The strength of those she photographed kept her going. “If they can wake up every morning and fight for their most loved ones that are in the darkness, then I have to wake up in the morning and do it for them,” she told The Media Line. “Through the devastation, you really see the strength of the people.”

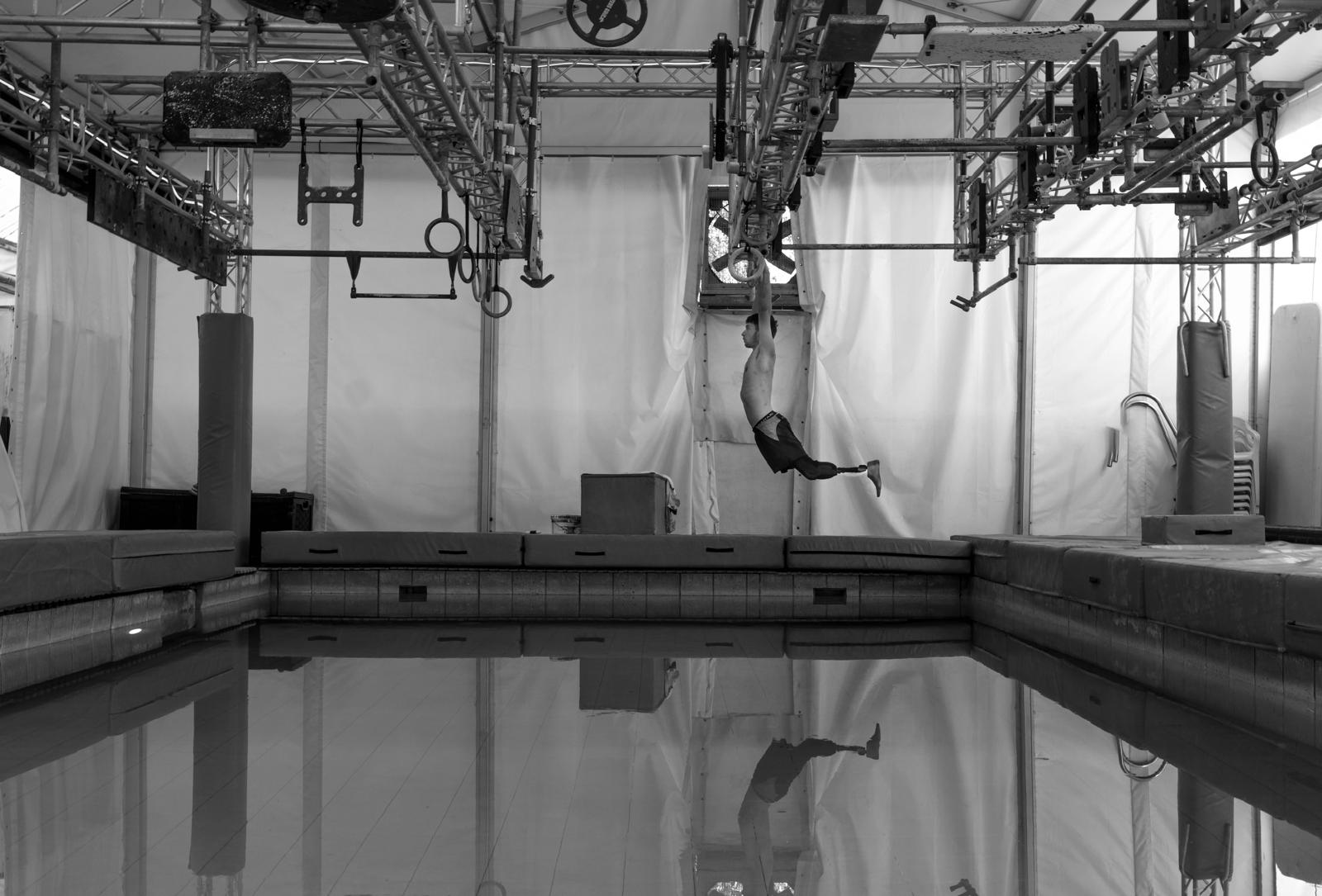

One image near the end of her book captures that strength. “This is Rachel and Jon [the parents of Hersh Goldberg-Polin],” she pointed out. “There’s this photograph of a soldier who is a double amputee. He’s only 22. And this is him doing—it’s called ‘ninja’ in Israel—but he just swings between these. It’s quite an incredible photo that I think the audience needs to understand. Quite the impact of the word you use—resilience—of someone saying, ‘I can do anything. And it doesn’t matter. Nothing’s going to stop me.’”

An IDF soldier, a double amputee, exercises on a ‘ninja’. (Courtesy Chen Schimmel)

The same spirit was present among evacuees returning to ruined homes and among Nova festival survivors. “I spent a few days at a Nova survivor party,” she said. “They’d been through absolute hell, but they were dancing again. That gives me the strength.”

Self-taught and never formally having studied photography, she inspires young people who believe they, too, can create something meaningful and lasting. Her photographs have already been exhibited around the world, and with her new book just launching, I asked what she hopes it will achieve.

“My hope for the book is truly for it to be in every Jewish home,” she said. “I know that that is a big dream or goal, but I truly believe it should be.” She added that even the day after the attacks, some people were already denying what had happened. “Then shouldn’t it be in not just Jewish homes?” I asked. “Well,” she said, “that’s even further. But for us as the Jewish people, to have our history documented and to show it to generations to come is extremely important.”

Schimmel, the granddaughter of a Holocaust survivor, said, “I actually showed her this book. She was one of the first to see it.” In the foreword, she wrote about her family’s story—how her grandmother’s family escaped from Poland, and how that legacy shapes her sense of purpose. “They didn’t have something like this,” she said. “For me, I’m really holding her story. It doesn’t just start on October 7th—it starts further back in my family’s history. That’s where it’s rooted from: to bear witness, so people can never forget or deny these events.”

Day to day, Schimmel works for The Jerusalem Post, and her reporting abroad includes work in Ukraine and Poland. Curious about what she had witnessed and the dangers involved, I invited her to share more about those experiences.

“It’s not simple,” she said. “People don’t understand that journalism is not an easy field. But if there aren’t people who are brave and willing to do this, then you don’t have documentation of the events of the world.”

She explained that her coverage of Ukraine came before her time at The Jerusalem Post when she was freelancing. “I just knew this was something I wanted to document,” she said. “Do you know the IFCJ—the International Fellowship for Christians and Jews? I went together with them as their photojournalist to document those being evacuated from the war zone. We were providing them with food and shelter.”

Schimmel said she had tried to get permission to go farther in. “I did try to convince them to go there,” she said, “but we were really more on the outskirts, receiving all those who were affected by this devastating war that’s gone on for far too long.”

IDF soldiers in Gaza. (Courtesy Chen Schimmel)

When I asked about the actual war zones she had worked in, she said, “That was here at home. In Gaza.”

What’s in store for Schimmel’s future? “Right now,” she said, “it’s to document the healing of the country—to document the hostages returning home and the soldiers coming home.” Looking ahead, she added, “It’s actually a dream of mine to travel to Africa. I’ve always loved Africa, and to document the wars going on there, the starvation, and the civil wars. It’s definitely something I hope to do—to document anything that tells its story. A story that, if undocumented, the world would not know of.”

Where can her book be found? “On my website, and also in bookstores—the main bookstores in Israel,” she said. “And in the upcoming month, we’re going to be selling the book in the States.”

She added that all proceeds will go to help soldiers coping with trauma. “I speak of finding light in the darkness,” she said, “but there are those who wake up every morning in the depths of darkness and don’t find that light. There are soldiers who wake up and can’t. Without them, we would not be here. It’s our job and our duty to heal them and to look after them, because they look after us.”