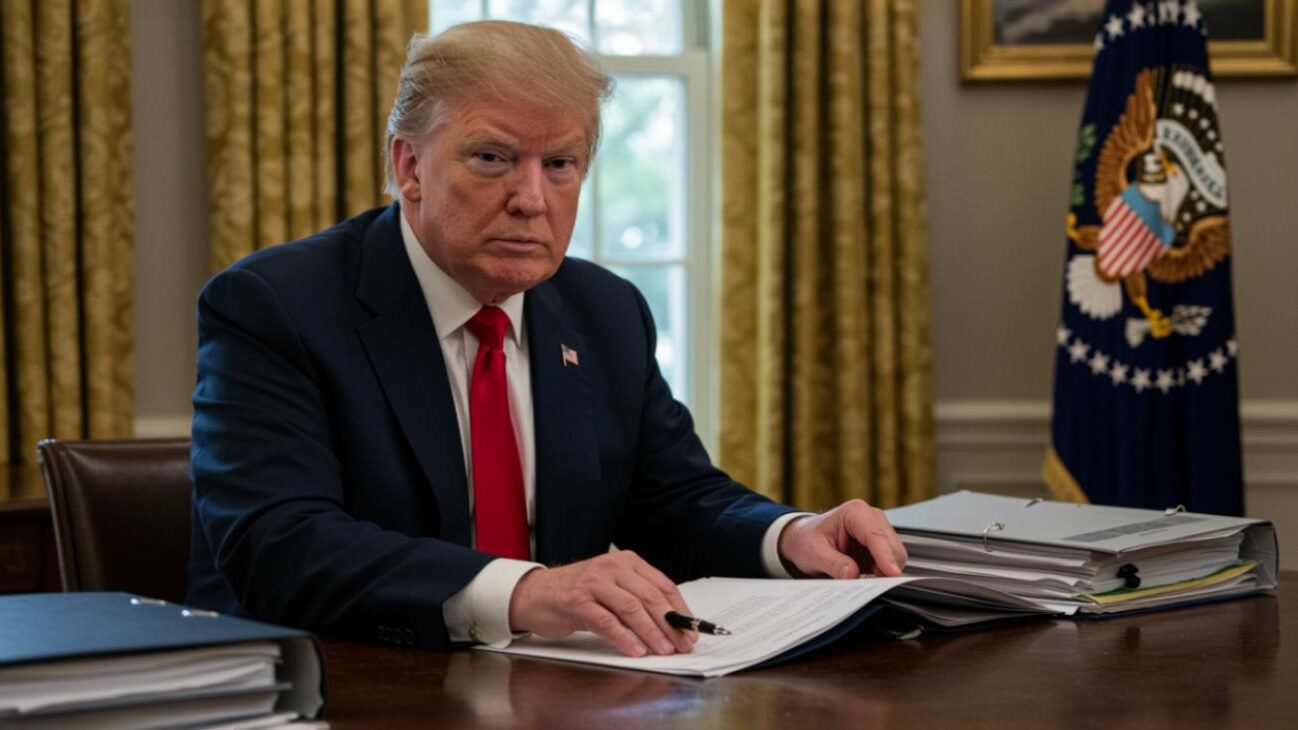

What Happens After Trump’s Muslim Brotherhood Executive Order?

El Watan, Egypt, November 28

US President Donald Trump signed an executive order initiating measures to classify certain branches of the Muslim Brotherhood as foreign terrorist organizations. The text of the decision asserted that these branches engage in or enable acts of violence or support campaigns aimed at destabilizing the country, thereby endangering US citizens and interests.

The order has triggered widespread reactions and raised questions about its implications for the global structure of the organization and its affiliated branches across several Arab countries. Trump’s move marks a significant shift in Washington’s approach toward the Muslim Brotherhood, transitioning from years of legal and political debate over the group’s nature to concrete executive action targeting specific branches found to be involved in violent activity or providing support to armed factions.

There is no doubt that the Muslim Brotherhood’s presence in the United States remains one of the most complex issues in the nation’s political and security landscape, particularly as controversy resurfaces whenever statements are issued by senior officials—most recently by President Trump and the governor of Texas—calling for the group’s designation as a terrorist organization. Although the Brotherhood never established an official, declared branch in the United States, its intellectual and organizational influence began to surface in the 1960s with the arrival of Arab and Muslim students, some of whom carried ideas rooted in the group’s literature and ideology. These students played formative roles in establishing student unions and Islamic associations that later became foundational to major Islamic institutions.

Give the gift of hope

We practice what we preach:

accurate, fearless journalism. But we can't do it alone.

- On the ground in Gaza, Syria, Israel, Egypt, Pakistan, and more

- Our program trained more than 100 journalists

- Calling out fake news and reporting real facts

- On the ground in Gaza, Syria, Israel, Egypt, Pakistan, and more

- Our program trained more than 100 journalists

- Calling out fake news and reporting real facts

Join us.

Support The Media Line. Save democracy.

During the 1970s, Arab immigration to America expanded, fostering new social and intellectual networks that adopted elements of the Brotherhood’s thought, even if not through explicit organizational affiliation. American research reports note that the Muslim Students Association was one of the most prominent spaces where this influence appeared, and several founders exposed to Brotherhood ideology contributed to shaping its early principles across US universities. Over time, the association evolved into a broader platform for Islamic activism, and some of its initiatives later grew into major institutions such as the Islamic Society of North America, now one of the country’s largest Islamic organizations.

Other groups also emerged, including the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR), which focuses on defending Muslim civil rights. Some researchers have linked CAIR to individuals with ideological ties to the Muslim Brotherhood, though all of these organizations firmly deny any formal connection. Despite the ongoing controversy surrounding these institutions, the White House has never issued an official finding confirming the presence of a unified Muslim Brotherhood entity operating within the United States.

However, the September 11, 2001 attacks sharply reshaped American perceptions of Islamic organizations. Several institutions came under investigation for alleged terrorism financing, and while individual members faced legal proceedings, no evidence emerged that would legally justify classifying the group as a terrorist organization. The issue remained a recurring feature in American political discourse until Trump entered the White House in 2017. The debate over designating the group resurfaced with renewed intensity, and Trump pledged during his campaign to consider such a designation. His administration continued to review the matter but ultimately issued no decision. At the time, media outlets citing security officials reported that the hesitation stemmed from concerns that the move could strain relations with countries that engage politically with Brotherhood-affiliated parties, combined with the challenge of establishing the existence of a unified global structure that could be prosecuted.

US institutions were also cautious about the possibility that such a designation might inadvertently sweep up dozens of American civil society organizations for which there was no evidence of wrongdoing. More recently, Texas Governor Greg Abbott’s decision to classify the Muslim Brotherhood and the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) as terrorist entities drew widespread attention on social media, becoming one of the most discussed posts on his official accounts. The reaction highlights the level of public support within the state and the breadth of the debate it ignited. Yet despite these developments, the United States has so far limited its terrorist designations to armed factions it believes maintain ties to Brotherhood members—such as the Revolutionary Brigade Movement and the Hasm Movement—without extending that designation to the Brotherhood itself. Amid ongoing upheaval in the Middle East and intensifying discussions within the United States about political Islam, the controversy surrounding the Muslim Brotherhood is likely to persist, particularly within American policy circles. That debate continues to revolve around a deep divide: between those who perceive the group as an ideological and security threat and those who argue that designating it without definitive evidence risks opening the door to unjustified scrutiny of the broader American Muslim community.

Khadija Hammouda (translated by Asaf Zilberfarb)